Dick Turpin

Dick Turpin’s romanticized image as the famed “Highwayman” of English lore was built on the big lie about his one-night ride from York to London on his faithful steed, Black Bess. Nor was he in any way a latter-day Robin Hood.

by Mark Pulham

“Stand and deliver,” Dick Turpin would shout, and with a brace of pistols levelled at the coachman, the romantic and reckless highwayman would relieve the passengers of their valuables. Dashing and daring, his tri-corn hat pulled low and a mask covering his face, he would flee on his gallant steed, Black Bess, into the night, his black cloak flowing behind him.

It’s an image that has been enhanced by numerous films going back to 1912, particularly by the Disney version and the 1970’s British television series. Who could ever forget his ride from London to York in a single night, his brave horse Bess dying from exhaustion to save his life? Who could not love the charming, handsome, courteous rogue that made robbery almost a pleasure? Certainly, this image of this latter day Robin Hood has passed down through the years with almost no change, thrilling generations of British schoolboys as the hero of numerous books. But is this an accurate portrayal of Turpin, was he really the handsome romantic hero we have seen in the movies? Hardly.

In the 18th century, highway robbery was a common event throughout Europe and Great Britain, and anyone foolish enough to venture into the woods after dark risked robbery at gunpoint and even death. For the most part, highwaymen were ordinary criminals, but in England, on occasion, they were gentlemen who were maybe down on their luck, or were in it for the adventure. Dick Turpin, however, was not a gentleman.

|

|

This 16th century historic country inn was the birthplace of Dick Turpin, the notorious highwayman, in 1705. |

John Turpin, a former butcher, was the landlord of the Bell Inn (now the Bluebell Inn) in Hempstead, Essex. It was here in 1705 that his wife, Mary Elizabeth Parmenter, gave birth to their fifth child, Richard, who was baptised on September 21of that year. By the time he was 16, he had received enough education to enable him to read and write, and was possibly apprenticed to a butcher in Whitechapel. During the next five years, Turpin’s life changed. First of all, he became a married man, taking Elizabeth Millington as his bride sometime around 1725. Secondly, his taste for the good life matured.

Around 1728, Turpin and his wife moved first to Thaxted, Essex, then to Enfield, where he set himself up as a butcher either in Buckhurst Hill or Stewardstone, both of which are now just on the outskirts of London. But business was poor, and Turpin’s extravagant lifestyle needed financing. It was a small step from butchering cattle to stealing them.

However, things didn’t always go according to plan, and two oxen that he had stolen were traced back to him. Turpin had got wind of the fact that his crime had been detected, and he escaped before he could be arrested, fleeing into the Essex countryside. His intention, it seems, was to head for the continent, but instead, he fell in with smugglers. This new career didn’t last long. Customs agents made it necessary for Turpin and the gang to lay low.

Soon, he was back on home ground, and now had joined the “Essex Gang,” also known as “Gregory’s Gang” after the three Gregory brothers, Samuel, Jeremy (or Jeremiah), and Jasper, who were the gang leaders. No doubt he had known of them before, they were notorious deer poachers, and who better than a young butcher to help them dispose of the stolen deer. Soon, he was stealing deer in what was then the Royal Forest of Waltham, now Epping Forest.

|

|

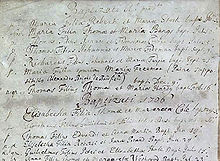

Dick Turpin's Baptism record (fifth one down). Reproduced by Essex Record Office. |

This was a dangerous game. In 1723, the Black Act came into force to deal with the poaching problem. It was so named after the practice of poachers to disguise themselves by blackening their faces. The rewards were small, and the risks were great. As with cattle stealing, deer poaching carried the death penalty.

Soon, a reward was offered. Anyone who helped identify the thieves would receive a £10 reward, and any thief who informed on his partners would be pardoned. With this sort of money involved, it was inevitable that someone would inform on them, and by October 1734, many of them had been caught or had moved away.

Poaching was now abandoned as a crime. Instead, the gang embarked on a new career, home invasion. They invaded the home of Peter Split, a chandler who lived in Woodford, and two nights later struck again in the same town, this time the home of Richard Woolridge. The actual identities of the invaders are unknown, but it is very likely that Turpin was amongst them. Over the next few weeks, several other home invasions occurred. The attacks were brutal, frequently involving beatings and threats to put the victim on the fire until told where the money was, a threat carried out in some cases.

At the beginning of February, 1735, at an inn on The Broadway, London, Turpin met up with Samuel Gregory and three other members of the gang, John Fielder, Joseph Rose, and John Wheeler. There, they planned a robbery, that of Joseph Lawrence, a farmer in Edgware. That afternoon, armed with pistols, they burst into Lawrence’s house, where they bound the maidservants and viciously attacked the 70-year-old man. Badly beaten, he had his pants pulled down to his ankles and they sat him on the fire until he told them where the money was. Gregory even raped one of the maidservants. The gang escaped with only £30. Three days later, along with two other members of the gang, Humphrey Walker and William Saunders, they committed a similar attack on a farm in Marylebone.

These attacks, prompted the 1st Duke of Newcastle, Thomas Pelham-Holles, to offer a reward of £50 for information that would lead to the arrest and conviction of the persons involved in the attacks. On February 11, Fielder, Saunders, and Wheeler were drinking in an alehouse, along with a woman who may have been Mary Brazier, another gang member who served as their fence. They were seen, and immediately arrested.

|

| E-fit of Dick Turpin created by York Police in 2009. Courtesy of York Castle Museum. |

Wheeler, who was very young, possibly around 15 years old, swiftly turned informer. He gave descriptions of his comrades which were then circulated. Turpin, according to Wheeler, was a “tall fresh coloured man, very much marked with the small pox, about five feet nine inches high.” In July of 2009, an E-fit was made of his face for the York Castle Museum. (An E-fit is an electronic picture of a person's face made from composite photographs of facial features, created by a computer program. In Turpin’s case, the E-fit was made based on eyewitnesses accounts of his face.)

Wheeler’s confession reached the ears of the gang, and most members fled. On February 15, Turpin and three other gang members, most likely Samuel Gregory, Thomas Rowden (or Rawdon), and Herbert Haines, robbed a house in Chingford, and the next day, Turpin and Rowden split with the other two, Turpin and Rowden heading for Hempstead where Turpin visited his family.

The Essex Gang, now missing several members and hunted by the authorities, kept a low profile, hiding most likely in Epping Forest. Joseph Rose, Humphrey Walker, and Mary Brazier were captured several days after Wheeler’s confession, and during the last week of February, Rose, Fielder, Walker, and Saunders were tried for burglary. Although absent, Gregory and Turpin were also named on the indictment.

On March 10, Fielder, Rose, and Saunders were taken to Tyburn, where they were hanged. Walker had already died in prison. All four bodies were hung in gibbets, Walker’s in chains, along Edgware Road, where they were left to rot.

Turpin and four remaining members of the gang performed another robbery in early March, but the gang’s end was fast approaching. Jasper Gregory was caught, tried and executed in late March, and his brothers were caught in early April in Rake, West Sussex. During this capture, Jeremy was shot in the leg and Samuel lost the tip of his nose in a swordfight. Jeremy died in jail, and Samuel, tried in May, was hanged on June 4. His body was hanged in chains next to his companions on Edgware Road. Haines was caught on April 13, found guilty and hanged in August, and Mary Brazier was transported. John Wheeler, thanks to his confession and help in capturing the other members of the gang, was freed. In January of 1738, he died in Hackney. What he died from is unknown, but it is assumed that it was natural causes.

Turpin now began the career that would make him famous. Along with Thomas Rowden, he became a highwayman. On July 10, 1735, the two robbed a gentleman between Wandsworth and Barnes Common. Though they may have been committing highway robbery since early April, this was their first recorded exploit. Several days later, they struck again, this time in Epping Forest. The reward for their capture had now reached £100.

They continued their robberies through the rest of the year, robbing a coach party of five in Barnes Common, and shortly after, between Putney and Kingston Hill, another coach party. They attacked and robbed a Mr. Godfrey on August 20 on Hounslow Heath.

The two stayed together until the winter of 1735, but then separated. Rowden, using the alias Daniel Crispe, was captured and convicted of passing counterfeit money. As Rowden, he had previously been found guilty of counterfeiting, and when Crispe’s true identity became known, he was transported in June 1738.

Turpin vanished from sight for a while, possibly going to Holland until he felt it was safe to come back. In February 1736, after his return, he was travelling on the London to Cambridge Road when he saw a well-dressed gentleman on a very fine horse. Turpin drew his pistol and told the man to hand over his money. Turpin was surprised when the man started laughing. According to legend, the man then said, “What, dog eat dog? Come Brother Turpin. If you don’t know me, I know you and shall be glad of your company.”The intended victim was Matthew “Captain Tom” King, also known as “The Gentleman Highwayman.” one of the most famous highwaymen at that time. Turpin had found himself a new partner.

They found a cave in Epping Forest between the King’s Oak and Loughton Roads that was large enough to hold their horses and themselves, which afforded a view of the roads through the forest yet kept them hidden from sight. From here, they could spot any number of victims.

The two men were unlike each other. King was a gentleman, dashing and reckless, while Turpin was basically a thug. At one point, while in Bungay, Suffolk, the two came across a couple of young women who had just sold some livestock in town. Between them, the women had £14 and Turpin decided to rob them. King, the gallant gentlemen, said they were too pretty to rob, and wanted to let them go. Turpin, however, was not in agreement, and took their money.

The successful partnership continued into 1737, and by this time, had an additional member of the team, Stephen Potter. The three men were certainly responsible for a series of robberies between March and April.

At this point, they did something stupid. In May of that year, they were travelling toward London and had reached a point close to the Green Man public house in Leytonstone. Turpin, King, and Potter caught up to a Joseph Major who was travelling the same road. They stole Major’s horse, which would not be unusual if it wasn’t for the fact that the horse, named White Stocking or Whitestockings, was a moderately well known racehorse and very recognizable. Turpin and his comrades had to have known this, yet arrogance or recklessness made them carry on with the theft.

Major rushed to the Green Man where he informed the landlord, Richard Bayes, about the robbery, swearing that it was Turpin who had committed the crime. Bayes traced the horse to the Red Lion in Whitechapel, and he got Major to come and identify the horse. Bayes and some constables lay in wait to see who would collect the horse.

Accounts differ on what happened next. Some say King’s brother came to collect the horse, others say it was King himself. According to Bayes’s own account, in his The History of the Life of Richard Turpin (1739), it was King’s brother, and once he was caught, he said that was just picking up the horse for someone else. Pressed for information, he said it was for a “lusty man in a white duffel coat waiting for it in Red Lion Street.”Bayes rushed to Red Lion Street where he attacked the waiting Tom King in the hopes of restraining him and “King immediately drew a pistol, which he clapp'd to Mr. Bayes's breast; but it luckily flash'd in the pan; upon which King struggling to get out his other, it had twisted round his pocket and he could not. Turpin, who was waiting not far off on horseback, hearing a skirmish came up, when King cried out, Dick, shoot him, or we are taken by G—d; at which instant Turpin fir'd his pistol, and it mist Mr.. Bayes, and shot King in two places, who cried out, ‘Dick, you have kill'd me;’ which Turpin hearing, he rode away as hard as he could. King fell at the shot, though he liv'd a week after, and gave Turpin the character of a coward.” Later reports, and Turpin’s own account, would state that the fatal shot that killed King was fired by Bayes himself.

Turpin fled and hid in Epping Forest, but he had not been unobserved. Thomas Morris was a servant working for Henry Thompson or Tomson, one of the Epping Forest keepers. Morris recognized Turpin and hoped to collect the large reward. On May 4, armed with pistols, he went to arrest the highwayman. He was not successful. When he challenged Turpin, according to the Newgate Calendar, “Turpin spoke to him in a friendly manner and gradually retreated at the same time, till, having seized his own gun, he shot him dead on the spot.”

The killing of Thomas Morris prompted the government to issue the following proclamation, which was published in The Gentleman’s Magazine of June, 1735. “It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, servant to Henry Tomson, one of the keepers of Epping-Forest, and commit other notorious felonies and robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious pardon to any of his accomplices, and a reward of £200 to any person or persons that shall discover him, so as he may be apprehended and convicted. Turpin was born at Thacksted in Essex, is about thirty, by trade a butcher, about 5 Feet 9 Inches high, brown complexion, very much mark'd with the Small Pox, his cheek-bones broad, his face thinner towards the bottom, his visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the shoulders.”

With this increase in bounty, Turpin decided the area was too hot for him and he headed north, ending up in Lincolnshire, where he rustled horses for a while, until arrested. He escaped, and made his way into Yorkshire, changing his name along the way to John Palmer. Here, he represented himself as a horse and cattle dealer, and gained some respectability. However, he was set in his ways, and his lifestyle still needed financing. So frequently, he was “away on business,” travelling back to Lincolnshire to commit more robberies and rustling.

In October 1738, Turpin had been on a shooting expedition, and foolishly, on the return home, shot and killed a game cock belonging to his landlord. For this, he was brought up in front of the magistrates. Refusing to pay the surety that was required, “Palmer” was sent to the Beverley House of Correction.

Suspicion began to grow about Palmer. His frequent trips away always resulted in him returning flush with money and with several horses. Authorities now made enquiries into how Palmer made his money, and it was discovered that John Palmer had been suspected of sheep stealing when he lived in Lincolnshire. Certain that they were dealing with someone whose criminal activities were a little more serious than the shooting of the game cock, authorities demanded sureties for his appearance at the assizes at York. Once again, Palmer refused, and was moved to York Castle.

A month passed, during which time three horses that Palmer had stolen were traced by the owner. Now it was clear that Palmer was a horse thief, and he was charged with this offence. Turpin believed that the charges against him would fail if he could find witnesses to swear to his good character. He wrote to his brother-in-law, Pompadour Rivernall, who was married to Turpin’s sister, Dorothy.

Dear Brother,

York, Feb. 6, 1739.

I am sorry to acquaint you, that I am now under confinement in York Castle, for horse-stealing. If I could procure an evidence from London to give me a character, that would go a great way towards my being acquitted. I had not been long in this county before my being apprehended, so that it would pass off the readier. For Heaven's sake dear brother, do not neglect me; you will know what I mean, when I say,

I am yours,

John Palmer.

Rivernall refused to pay the postage due on the letter. Some sources say that it was because he knew no one in York, some that he knew who was writing and wished to distance himself from Turpin. Yet others suggest that he was just tight-fisted. Whatever the reason, the letter was refused. By a stroke of bad luck, the letter was seen by James Smith, a former teacher who had taught Turpin how to write. Immediately recognizing the handwriting, Smith contacted the local magistrate, Thomas Stubbing, who paid the outstanding postage and opened the letter. Sure enough, Smith confirmed that the letter was indeed written in Turpin’s handwriting. Smith was sent to York to make a positive identification and did so on February 23. Smith collected the outstanding reward of £200.

With Palmer now revealed to be the infamous Dick Turpin, he became a celebrity and many visitors came to see him in jail. Turpin, kept in leg irons, was in high spirits and played to the gallery. Questions arose as to where the trial should take place. The Duke of Newcastle wanted the trial to take place in London, but authorities believed the risk of escape was too great and decided against moving the trial south. The trial would take place in York.

Turpin was charged, not with murder or his highwayman activities, but with the theft of the three horses belonging to Thomas Creasey, a mare and a gelding worth £3.00 each, and a foal worth £1.00. Horse stealing was a capital crime. On March 22, 1739, the trial began, Sir William Chapple presiding and Thomas Place and Richard Crowle prosecuting. At this time in England, anyone on trial had no right to any legal representation, and so Turpin was left to defend himself. He was asked if he had any questions for Creasey, he replied, “I cannot say anything, for I have not any witnesses come this day, as I have expected, and therefore beg of your Lordship to put off my trial ‘till another day.” Throughout the course of the trial, Turpin, claiming that he had not been given sufficient time to prepare his defense, continued asking for a delay so he could gather witnesses. But it fell on deaf ears.

Large bets were laid that he would not be convicted, but the evidence was clear. Turpin was found guilty of the theft of the mare and foal. A second trial followed, for the theft of the gelding. The jury brought in the guilty verdict and the judge pronounced the death sentence. Turpin’s father wrote a letter pleading for his son’s life, requesting that instead of death, he be transported. But the sentence stood, Dick Turpin would be hanged.

In the days leading up to the execution, Turpin bought some new clothes, including a frock coat cut from fustian cloth, and a pair of shoes. He also gave gifts and possessions to friends, including a ring to a married woman from Lincolnshire with whom he was acquainted. On the day before the execution he hired five men to act as mourners, for which he paid them ten shillings each.

The next day, Saturday, April 7, 1739, Turpin climbed into the cart that would take him on his last journey. With his mourners following, the cart made its way through York, with Turpin bowing to the spectators as he passed them.

The cart reached the gallows at Knavesmire, now part of York racecourse, and Turpin climbed the ladder to where the executioner waited. According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, “Turpin behaved in an undaunted manner.” Turpin felt his right leg start to tremble. To hide his fear, Turpin stamped his leg until the trembling stopped. He spoke to the guards and the executioner for about half an hour. Then, once the noose was in place, he threw himself off, and died within five minutes. And so, Dick Turpin, a smallpox scarred, violent criminal, ended his life with bravado.

The body was left hanging until the afternoon, when it was removed and taken to the Blue Boar Inn at Castlegate. It stayed there until the next morning, when it was taken to the graveyard of St. George’s Church in Fishergate. By the following Tuesday, according to reports, the body had been dug up by body-snatchers, a not unusual occurrence. The body was recovered, and re-interred, this time covered in quicklime.

So what of the Turpin legend? Certainly a lot of the legend came from the pamphlet written by Richard Bayes. Hastily put together to satisfy the public, it contains a mixture of fact and fiction, including a reference to Turpin having married a woman named Palmer, which is supposedly why he picked that name as an alias. However, according to biographers of Turpin, this is almost certainly wrong. In fact, Bayes account of Turpin’s life is highly suspect. Bayes’s involvement in the White stocking affair sounds like self promotion. King’s pistol misfires, sparing Bayes, and Turpin’s shot misses Bayes completely, killing King instead. Contemporary newspapers that initially published Bayes’s account of the events later retracted them. So, was it Bayes that actually fired the shot that killed King, and decided to cover himself by blaming Turpin? Quite likely. According to some sources, King was a popular figure, and shooting a popular figure cannot be good for business, or maybe he was afraid of retribution. In any case, the whole account of this incident is suspect.

But it is the ride from London to York on Black Bess that has been the centerpiece of Turpin’s legend. Did it really happen? Of course not, it’s impossible. York is 175 miles from London as the crow flies and 210 miles by roadway. But the account of this ride appeared long before Turpin’s life.

Between 1724 and 1726, the British author Daniel Defoe published a major work. A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain was a three volume account of his travels around the country, and includes an episode that mirrors Turpin’s ride. A highwayman named William (or John) Nevison robbed a man in Kent one morning in 1676. Realizing he needed an alibi, he took off at great speed, finally ending up in York that night. But even that story is probably not true.

The ride captured the imagination, and Turpin was associated with it at least as early as 1808. But it was Rookwood that solidified it in the public mind, and created the modern version of Dick Turpin. Rookwood was written by William Harrison Ainsworth and published in 1834. Turpin’s appearance in the book is that of a minor character, yet it was a popular one. Here, he was the romantic and dashing figure that we have come to know, and it appealed to the public. The ride to York was embellished and the legend was set. Turpin’s squalid violent past was erased, and the new Robin Hood-like version became the true character, and has remained ever since. Today, you can see his cell at York Castle Museum, which is well worth the visit.

Dick Turpin was transformed from a smallpox scarred horse and cattle thief, sheep stealer, murderer, torturer, house-breaker into a gallant, romantic, chivalrous protector of the weak. A Knight of the Road. It’s ironic that even in death he couldn’t resist one last piece of larceny. His legendary ride, his greatest feat, was stolen from someone else.