Lt. William Calley

Mini-My Lai massacres happened nearly every day in Vietnam, and thousands of war crimes were committed there by both sides in the conflict. In 1971, while the war was still raging, dozens of former American soldiers and Marines stepped forward to confess to the crimes they’d witnessed or participated in. Their harrowing testimony was part of the “Winter Soldier Investigation,” a truth commission sponsored by Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

by David Robb

Lt. William Calley was the only American ever convicted of a war crime in Vietnam. He is infamous for having led the 105 men of Charlie Company on a rampage through the village of My Lai, massacring more than 400 unarmed civilians, many of them women and children. Babies were bayoneted; teenage girls were raped in front of their parents and grandparents and then shot as they begged for mercy. Dozens of people were herded into an irrigation ditch and mowed down with automatic weapons. Many of the dead had been beaten and tortured first, and some of the bodies were found mutilated.

Testimony from his military trial revealed that Calley himself had killed more than 20 unarmed civilians, including a 2-year-old child, who Calley caught trying to escape the carnage. Calley grabbed the little boy by the arm, swung him into a ditch and dispatched him with a single shot. One of his men later testified that while he was standing guard over a group of more than 25 villagers, Lt. Calley approached him and ordered him to shoot them all. When he refused, Calley backed up a few steps and sprayed the wailing people with machinegun fire.

One soldier was so sickened by the slaughter that he shot himself in the foot to avoid taking part. He was the only American casualty that day.

But mini-My Lai massacres happened nearly every day in Vietnam, and thousands of war crimes were committed there by both sides in the conflict. In 1971, while the war was still raging, dozens of former American soldiers and Marines stepped forward to confess to the crimes they’d witnessed or participated in. Their harrowing testimony was part of the “Winter Soldier Investigation,” a truth commission sponsored by Vietnam Veterans Against the War, held in Detroit Michigan from Jan. 31 – Feb. 2, 1971.

These are some of their stories:

Chop, Chop

Joe Bangert was a Marine from Philadelphia assigned to the Marine Observation Squadron Six with the First Marine Air Wing in 1968. On his first day in Vietnam, he landed atDa Nang Air Base, and then took a plane to Dong Ha. From there, he hitch-hiked rides with military convoys on Highway 1 to his unit.

“I was picked up by a truckload of grunt Marines,” he testified. “We were about five miles down the road, where there were some Vietnamese children at the gateway of the village and they gave the old finger gesture at us. It was understandable that they picked this up from the GIs there. The trucks slowed down a little bit, and it was just like response, the guys got up, including the lieutenants, and just blew all the kids away. There were about five or six kids blown away and then the truck just continued down the hill. That was my first day in Vietnam.”

Sgt. Jack Smith was a highly decorated Marine sergeant from New Haven, Connecticut. When he first got to Vietnam in 1969, he and the other Marines in the 12th Marine Regiment, Third Marine Division, were sympathetic to the hungry little children they’d see running alongside their trucks, yelling “Chop, Chop” – meaning, “Give us food and candy” – as they convoyed though villages. The Marines would toss them candy and food – C-ration cans – so that the kids could eat, and to help win the hearts and minds of the innocent civilian population. But after months of bloody combat, that all changed.

“We began trying to hit them with the cans,” he testified. “We’d toss them into barbed wire and watch the kids go tearing after them, cutting themselves up. Some guys would drop the cans off the back of the truck when we were in a convoy. They’d drop the cans so the kids would have to dart out and grab them and try to get out of the way of the next truck. One of the kids didn’t get out of the way in time. The convoy just kept going. Every truck ran over that kid.”

James Duffy was a machine gunner on a CH-47 Chinook helicopter with Company A, 228th Aviation Battalion, 1st Air Cav. Division, who served in Vietnam from February 1967 to April 1968. He later recalled this incident of giving “food” to Vietnamese women and children.

“We’d throw out the C-ration cans that we didn’t like, and after they thought they were getting a lot of food, we’d hand them cans of 5606, which is helicopter hydraulic fluid, and very poisonous. And I observed one kid, that I handed a can of hydraulic fluid, take a good healthy drink out of it before his mother knocked it over, knocked it right out of his hand, and he was immediately sick right after that happened.”

Bill Hatton was a heavy equipment mechanic who joined the Marines out of high school in 1966. In Vietnam, he was assigned to the Engineer Maintenance Platoon at Dong Ha.

|

| Trioxane heat tab. Note warning: Harmful if swallowed. |

“I frequently traveled between Quang Tri and Dong Ha,” he recalled, “and we’d take C-ration crackers and put peanut butter on it and stick a trioxane heat tab (fuel used to heat rations) in the middle and put peanut butter around it and let the kid munch on it. Now they’re always looking for ‘Chop, Chop,’ and the effect more or less of trioxane is to eat the membranes out of your throat, and if swallowed would probably eat holes through your stomach.” He called this a “heat tab sandwich.”

Hatton also told the story of the little Vietnamese boy who used to taunt Marines driving by in convoys, yelling at them, “You Marines, Number 10” – meaning that they were bad men who didn’t give children food and candy. Good soldiers who gave the kids candy were called “Number One GIs!”

“We used to drive by this row of hooches (huts),” he recalled, “and a little 3-year-old kid in a dirty gray shorts used to run out and scream, ‘You, Marines, Number 10,’ and we’d always go back, ‘Oh fuck you, kid,’ and all this stuff. So one night the kid comes out and says, ‘Marines, you Number 10,’ and throws a rock. So we figured we’d get him because this was a way of having fun. The next night before we went out we all stopped by COC (Combat Operations Center), which is right by the ammo dump, picked up the biggest rocks we could get our hands on and piled them in the back of the truck. So when we left the Combat Base we just turned the corner and we saw a little kid, we were waiting for the kid – he ran out of the hooch – and he was going to scream, ‘Marine Number 10,’ and we didn’t even let him get it out of his mouth. We just picked up all the rocks and smeared him. We just wiped him out. In fact, the force of the rocks was enough to knock over his little tin hooch as well. I can’t say that the kid died, but if it would have been me, I would have died easily. The rocks, some of them, were easily as big as his head. It was looked upon as funny. We all laughed about it.”

He also recounted this story: “In March of ‘69, I was serving as security in a convoy, they just gave me a ride at the gate and we got four miles south of the Dong Ha perimeter and there were a group of Vietnamese women and children who were gathered around at this little bridge outposts the ARVNs (South Vietnamese military) had as security on Highway 1 there. The truck was doing considerable speed and it was just sort of spontaneous reaction, they said, ‘Let’s get ‘em. They want Chop, Chop, we’ll give it to ‘em,’ picking up cases of C-rats which weigh up to approximately 30 pounds and threw them off into the women and the kids. You know, just flattened them out and knocked them back quite a few feet. There was no way of determining whether or not they were actually dead but the injuries must have been serious.”

“My commanding officer once fired at a group of kids merely because they came up to our hill to collect C-rations,” recalled John Beitzel, a squad leader with the 11th Brigade, 4/21 Infantry. “We were also ordered to fire gas grenades at them. There was a big pressure for body count. We had a very low body count in our company and we had a lot of pressure coming down from the battalion commander to the company commander, down on to us. We were given new incentives to get a higher body count such as a six-pack of beer or a case of soda. And sometimes, a three-day pass, you know, for the amount of body count we had.”

“My commanding officer once fired at a group of kids merely because they came up to our hill to collect C-rations,” recalled John Beitzel, a squad leader with the 11th Brigade, 4/21 Infantry. “We were also ordered to fire gas grenades at them. There was a big pressure for body count. We had a very low body count in our company and we had a lot of pressure coming down from the battalion commander to the company commander, down on to us. We were given new incentives to get a higher body count such as a six-pack of beer or a case of soda. And sometimes, a three-day pass, you know, for the amount of body count we had.”

Robert McConnachie was 18-year-old high school graduate from Florida when he enlisted in the Army in 1967. He was a sergeant E-5 in Vietnam in 1968 with the 1st Infantry Division, 2nd/28th, Black Lions, when he witnessed several children killed by fellow soldiers playing the C-ration can game.

“When I was out in the field outside of Lai Khe with the infantry,” he recalled, “we were moved north, so some of us had to go by slicks, which are helicopters, and some by trucks, or jeeps, to Quan Loi, to re-supply the people who left before us. On the way up to Quan Loi, we were on Highway 13, you go through villages and you see little kids with their hands out, begging. Well, at first I saw GIs tossing the cans out to them, C-ration cans. Then all of a sudden I saw they were coming pretty fast at the children, and I saw two or three of them killed right there, stoned with C-ration cans. We were stopped by the MPs; he just warned us, so we kept on with our convoy and nothing was said about the kids.”

“It wasn’t like they were humans. We were conditioned to believe that this was for the good of the nation, the good of our country, and anything we did was okay.”

Jamie Henry was 19 when he was drafted into the Army on March 5, 1967. In Vietnam, he served with the 4th Infantry Division.

“On August 8th (1968), our company executed a 10-year-old boy,” he testified. “We shot him in the back with a full magazine M-16.

“Approximately August 16th to August 20th, I’m not sure of the date,” he continued, “a (Vietnamese) man was taken out of his hooch sleeping, was put into a cave, and he was used for target practice by a lieutenant, the same lieutenant who had ordered the boy killed. Now they used him for target practice with an M-60, an M-16, and a .45. After they had pretty well shot him up with the 60, they backed off aways to see how good a shot they were with a .45 because it’s such a lousy pistol. By this time, he was dead.

|

|

| Vietnam War-era APC |

“On February 8th (1969), this was after a fire-fight and we had lost eight men, we found a man in a spider hole. He was of military age. He spoke no English, of course. We did not have an interrogator, which was one of the problems in the fields. He was asked if he were VC and, of course, he kept denying it, ‘No VC, No VC.’ He was held down under an APC (armored personnel carrier) and he was run over twice – the first time didn’t kill him.” (The second time did.)

“About an hour later,” Henry recalled, “we moved into a small hamlet, this was in I Corps, it was in a Marine AO (area of operation), we moved into a small hamlet. Nineteen women and children were rounded up as VCS – Viet Cong Suspects – and the lieutenant that rounded them up called the captain on the radio and he asked what should be done with them.

“The captain simply repeated the order that came down from the colonel that morning, which was to kill anything that moves, which you can take any way you want to take it.

“When the captain told the lieutenant this, the lieutenant rang off. I got up and I started walking over to the captain thinking that the lieutenant just might do it because I had served in his platoon for a long time. As I started over there, I think the captain panicked, he thought the lieutenant might do it too, and this was a little more atrocious than the other executions that our company had participated in, only because of the numbers. But the captain tried to call him up, tried to get him back on the horn, and he couldn’t get ahold of him. As I was walking over to him, I turned, and I looked in the area. I looked toward where the supposed VCS were, and two men were leading a young girl, approximately 19 years old, very pretty, out of a hooch. She had no clothes on so I assumed she had been raped, which was pretty SOP (standard operating procedure), and she was thrown onto the pile of the 19 women and children – and five men around the circle opened up on full automatic with their M-16s. And that was the end of that.”

Mark Lenix was a 21-year-old lab technician when he was drafted into the Army. He went to officer candidate school and landed in Vietnam in 1968 as a first lieutenant, assigned as a forward observer with the 1st/11th Artillery attached to the 2nd/39th Infantry Battalion.

“In November ’68,” he recalled, “in an area called the Wagon Wheel just northwest of Saigon, while on a routine search and destroy mission, (helicopter) gunships which were providing security and cover for us in case we had any contact were circling overhead. Well, no contact was made, and the gunships got bored. So they made a gun run on a hooch with mini-guns and rockets. When they left the area, we found one dead baby, which was a young child, very young, in its mother’s arms, and we found a baby girl about 3 years old, also dead.

“Because these people were bored; they were just sick of flying around doing nothing. When it was reported to the battalion, the only reprimand was to put the two bodies on the body count board and just add them up with the rest of the dead people. There was no reprimand; there was nothing. We tried to call the gunship off, but there was nothing you could do. He just made his run, dropped his ordnance, and left.

“And there they were, man. The mother was, of course, hysterical. How would you like it if someone came in and shot your baby? And there was nothing we could do, man, we just watched it. And nothing happened. I have no idea what happened to the helicopter pilot, or to anyone in the gunship. It was gone.”

“We went mad when Pierce got blown away,” recalled Sgt. Michael McCusker, of Portland, Oregon, who served with the First Marine Division in Vietnam from 1966 to 1967. “A sniper hit him. The shot came from a village we just passed, and I turned around and saw this old priest standing there. Someone shot a gun right behind me and shoved that little priest right into his altar. Then we wiped out that village and another. I mean everything – we shot people, pigs, dogs, geese – we burned every hut. It was just madness.”

(The Vietnam War Memorial lists 50 Americans killed in the war with the last name Pierce.)

Charles Stephens was an Army private first class from Fords, New Jersey, and in 1967 was attached to the 27th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division, in Vietnam. His unit had taken numerous casualties in a battle in a place they ironically called Happy Valley, and the next day, they went into a village called Tuyhoa, and started shooting the place up, killing and wounding many civilians.

“The next morning,” he recalled, “we were camped on a hill above the village and the villagers were having a burial ceremony. This sergeant and a Spec/4 started firing machine gun rounds at the burial ceremony. They hit a guy, and people didn’t even look to see if he was dead. They just rolled him over and put him in the hole with the others and covered him up.

“We went down that same day to get some water and there were two little boys playing on a dike and one sergeant just took his M-16 and shot one boy at the dike. The other boy tried to run. He was almost out of sight when this other guy, a Spec. 4, shot this other little boy off the dike. The little boy was like lying on the ground kicking, so he shot him again to make sure he was dead.”

Jon Drolshagen was an Army 1st lieutenant from Columbus, Ohio, attached to the 9th Infantry, 25th Infantry Division, in Vietnam from 1966-67. Torturing suspected Viet Cong, he recalled, was routine.

“We’d attach wires to parts of their bodies,” he recalled. “The wires ran to a 12-volt Jeep battery. They would give off a pretty good scream when we stepped on the gas. If the wire method failed, the major in charge got out his knife. Once he just filleted a man alive, cut strips off him like bacon. We had to kill him after that – you couldn’t take a guy in that condition to a hospital.”

Sgt. Scott Camil, of Gainesville, Florida, was an advance artillery spotter in Vietnam attached to the Eleventh Marine Regiment, First Marine Division. “I could call in artillery whenever I saw fit. All I had to do was report incoming fire and I could get it. What we’d do is, if there was a slow time, we’d just pick out a village and say, “Okay, let’s see how many shots it takes to destroy this house.” And I’d call in artillery until I’d destroyed it. And then the mortar guy would call mortar rounds in until he destroyed one. And whoever used the least amount of rounds would win. The loser would buy the winner beers.”

He also told this story: “If an operation was covered by the press there were certain things we weren’t supposed to do, but if there was no press there, it was okay. I saw one case where a woman was shot by a sniper, one of our snipers. When we got up to her she was asking for water. And the Lieutenant said to kill her. So he ripped off her clothes, they stabbed her in both breasts, they spread-eagled her and shoved an E- tool up her vagina, an entrenching tool, and she was still asking for water. And then they took that out and they used a tree limb and then she was shot.

“It wasn’t like they were humans. We were conditioned to believe that this was for the good of the nation, the good of our country, and anything we did was okay.”

Joe Bangert, the Marine who saw five or six children intentionally murdered on his first day in Vietnam, also tells this story:

“In Quang Tri City I had a friend who was working with USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and he was also with CIA. We used to get drunk together and he used to tell me about his different trips into Laos on Air America Airlines and things. One time he asked me would I like to accompany him to watch. He was an adviser with an ARVN group and Kit Carson Scouts (former Viet Cong working for the U.S.). He asked me if I would like to accompany him into a village that I was familiar with to see how they act. So I went with him and when we got there the ARVNs had control of the situation. They didn’t find any enemy but they found a woman with bandages. So she was questioned by six ARVNs and the way they questioned her, since she had bandages, they shot her. She was hit about 20 times. After she was questioned, and, of course, dead, this guy came over, who was a former major, been in the service for 20 years, and he got hungry again and came back over working with USAID. He went over there, ripped her clothes off and took a knife and cut, from her vagina almost all the way up, just about up to her breasts and pulled her organs out, completely out of her cavity, and threw them out. Then, he stopped and knelt over and commenced to peel every bit of skin off her body and left her there as a sign for something or other.”

Kenneth Ruth was an Army medic in Vietnam who not only witnessed atrocities, but also participated in them. “Each of us could go on all day talking about atrocities that we witnessed,” he said. “Each of us saw many, and many of them we all participated in.”

One war crime he was involved in – the torturing of two villagers suspected of being Viet Cong – took place after the Special Forces unit he was attached to had entered a village and asked the villagers to point out who the Viet Cong were.

“Somebody had to be pointed out,” he recalled, “and the villagers weren’t going to point out themselves.” So two villagers were selected as VC suspects and tortured.

|

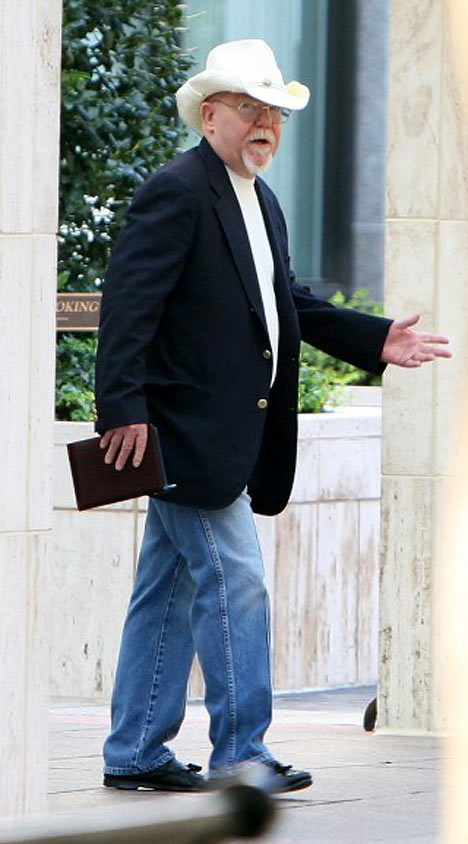

| William Calley today lives in Atlanta, Georgia |

“We were given two people that we were told were Viet Cong,” he said. “We took these two guys out in the field and we strung one of ‘em up in a tree by his arms, tied his hands behind him, and then hung him in the tree. A Special Forces man was running the whole show, and this is all under their command and everything. Now what we did to this man when we strung him up is that he was stripped of all his clothes, and then they tied a string around his testicles and a man backed up about 10 feet and told him what would happen if he didn’t answer any questions the way they saw fit. So they’d ask the guy a question: ‘Do you know of any enemy units in this area?’ And if he said, ‘No,’ the guy that was holding that string would just yank on it as hard as he could about 10 times, and this guy would be just flying all over the place in pain. And this is what they used. I mean anybody’s just going to say anything in a situation like this.

“Then we took the other guy to the other end of the village, and we didn’t do this, all we did was burn his penis with a cigarette to get answers out of him.

“This is just one of the things I saw. I could just go on all day. All of us could. But it’s not just us. Everybody knows this. It isn’t just Lieutenant Calley. I was involved, I know there are so many other people involved in all this American policy in Vietnam.”

But Lt. William Calley was the only person convicted of war crimes in Vietnam.

On March 29, a military court martial found him guilty of the premeditated murder of 22 Vietnamese civilians, and on March 31 he was sentenced to life in prison and hard labor at Ft. Leavenworth.

The next day, however, President Richard Nixon ordered him transferred from Leavenworth to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he spent the next three-and-a-half years living in comfort under house arrest.

When he was released a free man by a federal judge in 1974, a Georgia congressman accompanied him on his flight home.