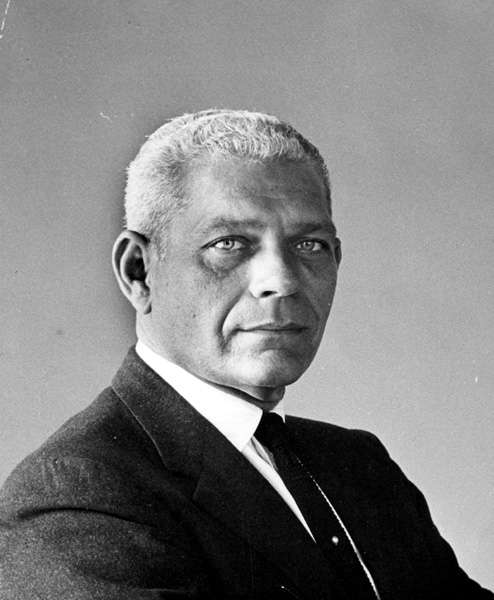

Clay Laverne Shaw

Clay Shaw's acquittal on conspiracy charges to assassinate President John F. Kennedy owes a great deal to his willingness to perjure himself at that 1969 trial.

by Don Fulsom

Clay Shaw (a.k.a. Clay Bertrand) holds the distinction of being the only individual ever tried as part of an alleged conspiracy to murder President John F. Kennedy. In 1969, after a 39-day trial, a New Orleans jury took less than an hour to find the wealthy local businessman not guilty.

Then 55, the tall, white-haired, distinguished looking Shaw was indicted and tried by a rather flamboyant ex-FBI agent—the parish’s controversial district attorney, Jim Garrison. The D.A. and his staff produced enough evidence to convince the jury there was a conspiracy—but the jurors said Shaw did not participate in it. Could the jury have been mistaken on Shaw? Looking at the case through history’s rear-view mirror, yes indeed.

Shaw was a military intelligence officer in World War II. His first post-war job was with a CIA proprietary, the Mississippi Shipping Company. At the time of his trial, Shaw was a director of Permindex, a Swiss firm suspected of not only being a CIA front, but of laundering money for organized crime.

He was also the director of the International Trade Mart in New Orleans—a position that entailed extensive foreign travel. It was not until 1996 that the CIA disclosed Shaw had obtained an agency security clearance as far back as 1949.

We now know the defendant (played by Tommy Lee Jones in Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK) lied under oath when he answered the most critical question of his trial: "Mr. Shaw, have you ever worked for the Central Intelligence Agency?" His response: "No, I have not.”

Shaw lied yet again—and even more boldly—after the trial, telling Penthouse: “I have never had any connection with the CIA.”

In 1979, however, former CIA Director Richard Helms acknowledged under oath that Shaw had been a contact in the CIA’s Domestic Contact Service.

As a CIA contact, Shaw used his cover as a businessman to feed the agency intelligence from his frequent foreign travels. JFK assassination researcher Martin Shackelford reports that Shaw’s CIA activities included a still-secret conspiracy that involved a future Watergate felon:

As late as 1967, Shaw had a "covert security" classification for a top-secret program called QKENCHANT. The program remains so highly classified that we are still unable to learn anything about its nature, but Shaw's classification was approved by the CIA's then covert operations chief, Richard Helms … Former CIA official Victor Marchetti said that QKENCHANT was most likely run out of the Domestic Operations Division of the Clandestine Services, headed by Tracy Barnes. Support for this comes from recently released documents identifying Barnes' then-deputy, E. Howard Hunt, as another individual involved with QKENCHANT.

A top CIA spy before he became a secret agent for President Nixon’s “black projects,” E. Howard Hunt has long been a JFK assassination suspect. In a deathbed confession, Hunt said he was in on the Dallas plot—but only as a “benchwarmer.” [A note of caution: Hunt was such a master of deceit and disinformation it is hard to give much credence to even his final words on earth.] Hunt died of pneumonia in Miami in 2007.

Nonetheless, if Hunt and Shaw had worked together on QKENCHANT, it seems fair to ask whether they might also have been key players in the murder of our 35th president.

Additional clues about a possible Shaw-Hunt connection might reside in a big pile of potential evidence still in government hands. The National Archives has yet to make public some 366 pages of CIA documents dealing with Hunt.

The CIA does not have an exemplary record in declassifying documents. So don’t expect to see these documents anytime soon. The agency also has a habit of blacking out much of the material it does reluctantly and eventually make public.

At Shaw’s trial, the defendant was shown a picture of the late David Ferrie—another prime suspect in the JFK assassination—and was then asked, “whether you have ever known this man?” Shaw declared, “No, I never have.”

Was Shaw dissembling again on the witness stand? According to many credible witnesses, he was. Several prominent citizens of Clinton, Louisiana, testified that they had seen Shaw in the company of Ferrie and Lee Harvey Oswald. Longtime Ferrie friend Raymond Broshears said he saw Shaw and Ferrie together a number of times; and a Ku Klux Klan member named Jules Ricco Kimble said Ferrie introduced him to Shaw. (Photographic evidence has since turned up showing that Ferrie and Oswald were friends.)

Vernon Bundy told the Shaw jury he had seen the defendant meet with Oswald at a seawall on Lake Pontchartrain in June 1963. (Shaw also swore at his trial that he never knew Oswald.) Mailman James Hardiman testified that he had delivered letters addressed to “Clay Bertram” to a forwarding address for Clay Shaw—and that none of the letters was ever returned.

Standing six-foot-six in socks, “Big Jim” Garrison was an imposing figure with a booming voice. His key witness was Perry Russo—then a 21-year-old insurance agent. Russo positively identified a photo of Clay Shaw as “Clay Bertrand.” He testified that, in September 1963, he had overheard Shaw discussing plans to assassinate Kennedy. Russo said others present were Ferrie and a man introduced to him as “Leon Oswald.”

Shaw’s defense team, led by F. Irvin Dymond, undercut Russo’s testimony by saying Garrison had drugged and hypnotized the witness to obtain his statement. The D.A. insisted Russo was hypnotized and given “truth serum” only to make certain of his honesty.

The speedy not guilty verdict strongly indicates the jurors bought the Shaw legal team’s major contentions, including this one. All the jurors agreed, however, that Garrison had proved that the President’s death resulted from a conspiracy.

For the rest of his life, Russo stuck to his story about being at a pre-assassination meeting attended by Shaw, Ferrie and Oswald. Years after the trial, in a videotaped interview, Russo remembered that "Ferrie was in control of the gathering … He was in one of his obsessive evenings concerning his hatred of the President of the United States."

A pilot for both the CIA and for New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello, Ferrie died on February 22, 1967—just as Garrison was about to indict him. Ferrie was found lying on a couch in his apartment with a sheet pulled over his still-bewigged head.

Two typed but unsigned suicide notes were found nearby. The first began "To leave this life, to me, is a sweet prospect." The second simply said that "when you read this I will be quite dead and no answer will be possible."

Metro Crime Commission director Aaron Kohn believed Ferrie was murdered. But the coroner ruled his death was natural—caused by a cerebral hemorrhage.

Clay Shaw did not live to bear the added burden of being exposed as a perjurer when the CIA, in 1979, finally admitted he had worked for them. He was carrying a heavy enough load when he died: despondency over a stack of unpaid legal bills and depression over his outing as a homosexual. A chain-smoker, Shaw died in 1974—apparently of lung cancer. He was buried before an autopsy could be performed.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sources include: Encyclopedia of the JFK Assassination; Who’s Who in the JFK Assassination by Michael Benson; Crossfire by Jim Marrs; A Farewell to Justice by Joan Mellen; Fair Play; Salon; and transcripts of Clay Shaw’s trial from the Mary Ferrell Web site.