Dr. Sam Sheppard

At his second trial, with young F. Lee Bailey as his defense attorney, Dr. Sam Sheppard was acquitted of his wife’s terrible murder. The famous case continues to fuel speculation more than a half century later.

by Denise Noe

Beaten to Death

Many points in the Sam Sheppard case remain in dispute but this is certain: in the wee hours of the Fourth of July in 1954, Marilyn Sheppard was beaten to death in her suburban bedroom.

Four months pregnant, pretty, brown-haired Marilyn Sheppard, 31, was married to her high school sweetheart, successful neurosurgeon Dr. Sam Sheppard, 29.

The couple resided in the Cleveland, Ohio suburb of Bay Village in a two-story house set on a high cliff overlooking Lake Erie.

Sam Sheppard is backed up by neighbors and close friends Spencer “Spen” and Esther Houk in his claim that he called their home at 5:40 that morning.

“My God, Spen, get over here quick!” Sam shouted. “I think they’ve killed Marilyn!”

Spencer woke his wife and they drove two doors to the Sheppard home. They drove because Spencer walked with difficult due to a bad knee. Spencer was a butcher who also served as Bay Village mayor.

The Houks entered the Sheppard's unlocked kitchen door. Inside the house, they found a shirtless Sam, his pants drenched in water, leaning against a chair in the den. He moaned as his hands pressed the back of his neck.

“What happened?” Spencer asked.

Sam said he had fallen asleep on the living room couch after last evening’s party only to be awakened by Marilyn screaming, “Sam!” Sam ran up the stairs where “somebody clobbered me.” He said he lost consciousness after being struck.

Esther rushed upstairs and found a scene of horror. As James Neff reports in The Wrong Man: The Final Verdict on the Dr. Sam Sheppard Murder Case, “on the bed . . . Marilyn’s body lay face up. Her legs hung over the foot of the bed. . . . under a wooden bar that ran from post to post across the foot of the bed. It looked as if someone had pulled her legs under the bar, pinning her like a giant specimen. Her body was outlined by blood. . . About two dozen deep, ugly crescent-shaped gashes marked her face, forehead, and scalp.” Marilyn’s pajama tops were pushed up to her neck so that her chest area was bared. There was a blanket around her middle. Underneath that blanket, her pajama bottoms had been partially removed so that her pubic area was exposed.

Esther checked Marilyn for a pulse – and found none. Then she ran back downstairs and yelled, “Call the police! Call the ambulance!”

Sam asked her to return upstairs and check on his and Marilyn’s son, 7-year-old Sam Jr., nicknamed “Chip.”

Esther found that the boy was sleeping soundly. Amazingly, he appeared to have slept through an extraordinary battle waged in the room across from his. Later it would be revealed that Chip, like his father, was an extraordinarily sound sleeper.

At about 6 a.m., Bay Village police officer Fred Drenkhan arrived at the Sheppard house. He noticed a doctor’s bag on the hallway floor, turned upside down with its vials and prescription pads in a mess. When Drenkhan entered the den, the police officer found Sam – and another mess. As Neff writes, “Two trophies lay on the floor, broken: one of Sam’s treasured high school track trophies and Marilyn’s bowling trophy.”

Drenkhan asked Sam what had happened and the doctor told a fuller version of the story he told the Houks. He had heard his wife cry out, ran upstairs, been clobbered and passed out. When he came to, he heard noises downstairs and ran down there and after someone. In this and subsequent conversations, he variously described that someone as “a light form” and “a bushy-haired man.” The form ran out of the house and Sam chased it, catching up with it on the sand. The pair fought and Sam was again knocked unconscious. When Sam came to, he was at the edge of Lake Erie, with his upper body in the sand and his lower body in the water.

Dr. Richard N. Sheppard, Sam’s oldest brother, arrived on the scene. Spen had called Richard to take Chip home with him.

A Bay Village police officer drove to the small farm of Bay Village Police Chief John Eaton. Eaton headed to the Sheppard residence.

Dr. Steve Sheppard, another Sheppard brother, drove up with his wife, Betty. Steve immediately thought that Sam had sustained a serious neck injury.

Steve drove Sam to the Bay View Hospital.

Who could Do This?

Chief Eaton phoned Cuyahoga County Coroner Dr. Samuel Gerber. Gerber phoned a close associate and the pair arrived at the Sheppard home around 8 a.m. Police Officer Drenkhan told Gerber what Sam said had happened. Gerber found Sam’s vague account alarmingly suspect. He also thought he saw evidence of a staged scene in the living room. Three drawers were pulled but not taken out of a desk and their contents were not thrown about. As he went upstairs, Gerber saw drops that appeared to be dried blood. There was also what looked like smeared blood on the doorjamb and knob plate of the door that led to the screened porch. That blood suggested that the person who opened it had a bloody hand and may have had a cut on it.

A technician from the Scientific Investigation Unit, Michael Grabowski, arrived on the scene at 8:10 a.m. Gerber pointed out objects and areas he thought relevant and Grabowski photographed them. Then Grabowski dusted for fingerprints. Later, Grabowski went to the beach where, according to Neff, Grabowski “photographed two sets of footprints, one of them barefoot.”

Gerber went to Bay View Hospital to interview Sam. Gerber then returned to the Sheppard house to find two Cleveland homicide detectives, Robert Schottke and Pat Gareau, already there. The three conferred and agreed this was probably a domestic homicide staged to simulate a burglary. They thought Sam had gotten rid of his T-shirt because it was covered with blood. They also believed he had plunged his lower body into the water to wash off blood. “It’s obvious that the doctor did it,” Gerber said.

However, the relative absence of blood on Sam’s clothes was puzzling. As Cynthia Cooper and Sam Reese Sheppard note in their 1995 book, Mockery of Justice: The True Story of the Sheppard Murder Case, “None of Dr. Sam’s clothes were spattered with blood: not his pants, not his leather belt. It’s hard to wash blood out of cloth (and even then it can be seen microscopically), but it is virtually impossible to remove blood from leather. The only blood on his clothing was a splotch, which matched perfectly a mark on the sheets where Dr. Sheppard said he had leaned over his wife to check her condition.”

Dr. Lester Adelson performed the autopsy on Marilyn Sheppard. He set her time of death between 3:30 a.m. and 5:30 a.m. with the most probable time being “at about 4:30 a.m.” Nevertheless, Gerber told reporters that she had died at about 3 a.m. This earlier time made Sam’s story especially suspicious. He had called the Houks at about 5:45 a.m. Observers naturally wondered what Sam had done in the two hours and forty-five minutes between his wife’s death and his attempt to seek help.

As Neff relates, Dr. Adelson found that “the killer had fractured her skull plates with 15 blows, but none of the strikes was powerful enough to push bone into the durra, which encased the cerebellum just under the bones.” This was significant for it suggested that either the killer was not physically strong or was deliberately dragging things out or had mixed feelings about the battering and so did not put full strength into it. Two teeth were torn out. Marilyn also had several injuries to her hands, including a fingernail torn off, that indicated she had fought hard for her life.

Perhaps because Adelson may have already heard that his superior, Gerber, was convinced this was a domestic homicide, he did not examine Marilyn’s vagina for the tearing that might indicate rape. He removed a male fetus from her womb and preserved it in a large jar.

Around the Sheppard residence, Gerber and Eaton gathered a group of neighbors to look around the area for a discarded weapon. Mayor Houk’s 16-year-old son, Larry, found a cloth bag. Among other things, it held a watch that had stopped at 4:15 a.m. Dried blood was on the band. The watch belonged to Sam Sheppard. This seemed to clinch Sam’s guilt. He claimed he did not check on his wife after being knocked unconscious, so how had the blood got there unless it had spattered while he was beating her?

At Gerber’s request, Dr. E. R. Hexter examined Sam and found that he had a few injuries, none of which were serious.

Dr. Charles Elkins examined Sam at the request of the Sheppards. Neff writes, “Elkins said that Sam had a cerebral concussion, a spinal cord injury that robbed him of reflexes on one side.” He also found that Sam’s neck went into spasms, a response impossible to simulate.

Sam’s family retained a respected attorney named Bill Corrigan. On the advice of Corrigan, Sam refused to take a polygraph test.

Sam and Marilyn

Newspapers related the Sheppard family’s history. Samuel Sheppard was born on December 23, 1923, the youngest of three sons. His parents were Dr. Richard Sheppard and Ethel Sheppard. The senior Richard Sheppard was a doctor of osteopathic medicine or D. O. Osteopaths are similar to allopathic physicians or M.D.s. As Cooper and Sheppard observe, “osteopaths would take the same or similar medical exams and had specialties, such as surgery or gynecology or pediatrics. Like M.D.’s, osteopaths served internships and residencies, prescribed drugs, and ordered X-rays.” However, they also note, “Osteopaths also believed in the integration of treatment, approaching the body as a whole and incorporating body manipulation with other treatments.”

Along with his brothers, Sam grew up in a Cleveland suburb.

The ambitious elder Dr. Richard Sheppard founded the Cleveland Osteopathic Hospital in 1935. He wanted each of his three sons to follow in his footsteps and grow up to be physicians but it seemed at first that Sam would disappoint his father.

In his elementary school years, Sam earned lackluster grades. In eighth grade, he became an outstanding athlete.

By the time he was in high school, Sam had developed a determination to become a doctor that led him to study hard. His grades rapidly improved.

After graduation, Sam went to Hanover College in Indiana. Sam accumulated about three years of undergraduate credits before attending the College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons in Los Angeles.

Marilyn Sheppard had been born Florence Marilyn Reese on April 14, 1923 into the affluent home of Thomas and Dorothy Reese. Thomas Reese was an inventor and the vice president of a Cleveland manufacturing company. Neff writes, “Among his inventions was a process to transfer a wood-grain look to metal, later used by carmakers for the decorative side panels of station wagons.”

|

|

| Marilyn Sheppard |

When Marilyn was in the first grade, her mother became pregnant. Dorothy died in childbirth as did her newborn son.

Unable to care for Marilyn at the same time as he struggled with his grief, Thomas sent his daughter to live with her Aunt Mary and Uncle Bud Brown. After a few years, Thomas married another woman and had his daughter move back in.

In junior high school, Marilyn and Sam met. They did not date each other exclusively but they saw each other through high school and after Marilyn graduated.

He and Marilyn wed on February 22, 1945.

After a difficult birth, Marilyn delivered Samuel Reese Sheppard on May 18, 1947.

Sam returned with Marilyn and little Chip to Cleveland to join his brothers in their practice.

The Days Before the Day of Doom

On July 1, 1954, a visitor arrived at the Sheppard residence. His name was Dr. Len Hoverstein. A close friend of Sam’s, Len had just been fired from a hospital. He asked to stay for a while and Sam agreed.

Marilyn was displeased by Len’s arrival. According to Cynthia Cooper and Chip Sheppard, Len had stayed at the Sheppard house before and Marilyn had found him “sloppy and inconsiderate.” Neff writes that Len had also made advances at Marilyn that she had rebuffed.

On Saturday, July 3, Len decided he wanted to spend the night with friends about 40 miles away. Cooper and Chip Sheppard speculate in their book that since Sam and Marilyn “were throwing a hot dog roast for the hospital interns on the next day,” Len “wanted to avoid the uncomfortable comments that might arise about his lack of job prospects.”

Thus, Len was gone when neighbors Don and Nancy Ahern arrived at the Sheppard home for a dinner party. Sam went to sleep on the daybed. The visiting couple left after midnight through the kitchen door. Neff writes, “Nancy later told the police that she could not remember locking the kitchen door. And, no, she could not remember if Marilyn had locked it either.”

A Philanderer Who Flaunted It, the Other Woman, and the Lie

Gerber, Schottke, Gareau and others were convinced that Sam had killed his wife. They soon believed they had a motive in a classic marital problem. Nancy Ahern revealed that Sam was frequently unfaithful and had been seeing a Bay View Hospital nurse. People speculated that Sam and Marilyn had gotten into an argument about his infidelity that had tragically escalated or that he had killed Marilyn so that he could be free to marry another woman. In 1954, a divorce was difficult to obtain if either husband or wife opposed it and still slightly scandalous.

Marilyn knew about her husband’s wanderings. At one point, they discussed divorce but Marilyn did not want to become a single mother.

Marital difficulties were exacerbated by Sam’s lack of discretion in pursuing extra-marital relationships. In his affair with nurse Susan Hayes, Sam flaunted their relationship. He and Marilyn attended an office Halloween party. At the party, Susan whimsically grabbed Sam’s pipe and put it in her mouth, saying she was in character as the doctor. The two of them openly flirted and Marilyn left the party.

During a working vacation in California in which Sam received advanced surgery training, Marilyn stayed apart from her husband to enjoy the natural beauty of Big Sur. Sam called Susan Hayes who soon joined him. He brought his mistress into the home of a friend with whom he was staying. Susan stayed in the bedroom Sam was using and was with him while his host and hostess socialized. Neff notes, “Most of the women there knew Marilyn and resented being put in such an uncomfortable situation by her husband.”

When Sam met up again with Marilyn, he told her that he definitely wanted to stay with her. She became pregnant during these days.

Investigators learned that infidelity might have sparked the killing in another way. They spoke to a neighbor who claimed Marilyn had said she could not get pregnant again because Sam was sterile due to X-ray exposure. The neighbor was unclear as to whether this was said in a serious or joking manner but if the former, it suggested that Marilyn might have been pregnant by another man and Sam had exploded in rage over it.

A laboratory attempted fetal blood typing of the fetus removed from Marilyn’s womb after her death. Such blood typing could not establish paternity but could rule particular men out. However, that blood typing was unsuccessful so nothing about its paternity could be established.

Spen was sometimes with Marilyn for coffee and Steven Sheppard suggested Spen had a romantic interest in her.

Neff reports that a woman named Jessie Dill told investigators that Marilyn was having an affair. Dill claimed the two of them had struck up a conversation and that Marilyn had confided that she had been seeing another man. Police found Dill’s account credible because it included specifics about the Sheppard marriage that had not been in the papers such as the name of one woman with whom Sam had been involved.

An inquest into the death of Marilyn Sheppard was held July 22, 1954.

Gerber summoned Sam. He asked him if he had had an affair with Susan Hayes. Sam stoutly denied it.

Trial by Press?

Louis Seltzer, editor of the Cleveland Press, was convinced of Sam’s guilt and Seltzer’s newspaper crusaded for Sam’s arrest. The paper ran an editorial entitled, “Why Don’t Police Quiz No. 1 Suspect?” That editorial asserted that Sam was receiving kid-glove treatment because he was an upper-middle-class doctor: “You can bet your last dollar the Sheppard murder would have been cleaned up long ago if it had involved ‘average people.’ They’d have hauled all the suspects to Police Headquarters. They’d have grilled them in the accepted, straight out way of doing police business.”

Other Cleveland Press headlines included “Why Isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?” and “Quit Stalling and Bring Him In!”

On July 30, 1954 Sam Sheppard was arrested as he walked out the front door of his house. Along with the police was an angry crowd taunting, “Murderer! Murderer!”

Sam Sheppard’s trial began October 28, 1954. Judge Edward Blythin presided. The lead prosecutor was John Mahon.

Corrigan headed Sam’s defense.

When Gerber took the stand, he made a startling assertion about the bloodstains on Marilyn’s pillowcase. Cooper and Chip Sheppard report that he testified that the stains “showed two blades, each about three inches long, joined in the middle like a wishbone, and separated at its widest part by two and three-quarters inches, each blade having a tooth like indentation at the end.”

Gerber asserted that the stains were made by an instrument. The prosecutor asked him to specify what type of instrument and the coroner answered, “A surgical instrument.”

On cross-examination, Corrigan asked if Gerber had compared the pillowcase stains to surgical instruments in the Sheppard home and Gerber replied that he had only done a “casual inspection” and could not identify any as the source of the stains. When asked if he had compared surgical instruments at Bay View Hospital to the stains, Gerber said, “No.”

Mary Cowan testified. On cross-examination, Neff writes, “Corrigan tried to use Cowan to counter the state’s theory that Sam had washed blood from himself by jumping into the lake.” Cowan conceded that microscopic traces of blood would remain on fabric even after being drenched in water. Neff elaborates, “Corrigan felt her revelation helped Sam’s case immensely. There should have been a few dozen spatters of blood on the front of Sam’s pants if he had killed Marilyn, not just one large stain at the knee.”

Prosecutors called Sheppard housekeeper Elnora Helms to the stand. She testified that police had asked her to examine the bedroom after the slaying and that she could find nothing missing from it. Neff writes that this indicated premeditation as the killer must have “brought the unknown murder weapon into the room” rather than having grabbed something available as might have been the case with a sudden explosion of temper.

Susan Hayes testified. A prosecutor asked what Sam had said about divorce. Hayes answered, “I remember him saying that he loved his wife very much, but not so much as a wife. He was thinking of getting a divorce, but that he wasn’t sure that his father would approve.”

The Defense Begins

Neff writes, “For their defense, Corrigan and Garmone followed the game plan outlined in opening statements: first, that Sam was not the kind of man who would kill, second, the evidence proved that he could not have done it; and, finally, evidence pointed to a third party at the crime scene – in particular two independent witnesses who saw a strange man near the Sheppard home about the time of Marilyn’s murder.”

Dr. Richard Sheppard testified that it would have been impossible for someone to batter Marilyn as she had been battered without getting the clothing on his lower body splattered with blood.

Two witnesses testified they had seen a man with bushy hair in the vicinity in that early morning.

Dr. Sam testified to running upstairs to see a “form” and chasing “it’ to the beach. Then he seemed to have a clearer view and described the “person” as having “a good-sized head – with a bushy appearance at the top of his head – his hair.”

On cross-examination, Mahon asked Sam repeated questions about his extra-marital affairs.

The cross-examination ended with the following exchange.

Mahon: Doctor, what is the best way to remove blood from clothing?

Sam: I couldn’t tell you, sir.

Mahon: Is cold water more effective to remove blood from clothing than hot water?

Sam: I am certainly no authority on that, and I have never tried to remove blood from clothing, sir.

Mahon: Now, Doctor, the injuries that you received, didn’t you receive those injuries from jumping off of the platform down on the beach?

Sam: No, sir, I think that would be impossible.

The defense called Dr. Charles Elkins. He testified that Sam had been severely injured. Normal reflexes had been missing from his left side and when his neck was pressed his muscles had gone into involuntary spasms. However, the reality of his injuries did not necessarily exculpate Sam as Marilyn could have injured him in their struggle or he could have injured himself, as the prosecution suggested, in a suicide attempt after killing her.

Closing Arguments and the Verdict

Tom Parrino made the first closing argument for the prosecution. Parrino stated: “If this was a burglary, then this was the neatest burglar in history.” He pointed out that Sam was large and strong and asked incredulously, “This man was rendered senseless with a single blow?”

Pete Petersilge led off the defense closing. He said, “The state still does not know with what weapon she was killed, the state still doesn’t know why she was killed. And yet on the basis of that rather flimsy evidence, the State of Ohio is asking you to send Sam Sheppard to the electric chair.”

Petersilge argued, “If Sam had then tried to cover up, he could have done a lot better than he did. . . It certainly would have been a very easy thing to put on another T-shirt.” He continued that the lack of blood on Sam’s belt, shoes, and socks constituted “mute evidence, but very powerful evidence, that Sam Sheppard did not kill his wife, because the person who killed Marilyn” would have to have been heavily sprayed with blood.

Mahon said Sam had injured his neck when he flung himself into the water in a suicide attempt, “pursued by his own conscience as he ran away from the foul act that he had just committed.”

Judge Blythin told the jury that they had five possible verdicts: not guilty, manslaughter, second-degree murder, first-degree murder with a recommendation for mercy, and first degree murder minus the recommendation for mercy. About the final option, Blythin reminded them, “If you do find the defendant guilty of murder in the first degree and do not recommend mercy, it will be the obligation of the court to sentence the defendant to death.”

The jury deliberated five days. On December 21, they found Sam Sheppard guilty of murder in the second degree. Judge Blythin sentenced him to life imprisonment.

Enter Criminalist Dr. Paul Kirk

After the conviction, Corrigan sought the help of Dr. Paul Kirk in finding grounds for appeal. Neff writes that Kirk was “known as the founding father of criminalistics, a term he coined.”

Kirk agreed to research the Sheppard case but warned Corrigan that he would follow the evidence wherever it led and that Kirk would not shape his findings to reach any particular conclusion. In fact, Kirk’s initial impression was that Sam was guilty. He found Sam’s amorphous description of the intruder suspicious and thought the neatly pulled out drawers indicated staging.

Kirk arrived in Cleveland on January 22, 1955. At the Sheppard house, Kirk vacuumed the floor of the bedroom in which the murder had taken place with a special instrument that, as Neff writes, possessed “a customized filter to trap minute particles.” He took multiple photographs and made measurements.

After closely studying the blood patterns on the walls, Kirk found a gap in the blood spatter. He believed this gap was accounted for by blood having spattered on the person of the killer. He thought the weapon had been roughly a foot in length.

There was one blood spot that Kirk believed stood out from all others. Neff notes, “It was the largest by far, one inch in diameter and nearly round. It adhered to the lower third of the wood closet door, about three feet from where Marilyn’s head rested, and did not display the beading characteristic of impact spatter.”

Still troubled by Sam’s vague description of the intruder, Kirk tested the story. At night, Kirk had Dr. Richard dress in a white shirt and dark pants and stand at the foot of the bed. All lights were off save a dim one in the dressing room. Kirk ran upstairs. Cooper and Sheppard write that Kirk saw “a whitish ‘form,’ exactly as Dr. Sam described it.”

Kirk went to the prosecutor’s office and examined the spatter on Marilyn’s pajama bottoms. He concluded that they were already pulled down at the time of the battering and believed that indicated sexual assault. Large parts of Marilyn’s teeth had broken off. He believed it unlikely her teeth were broken by her face being battered because she had no swelling around her lips. Rather, Kirk thought she had bitten down on her attacker’s hand. Experiments in his laboratory led him to think that the puzzlingly unique spot on the wall was made from a bleeding wound.

Kirk believed many of the blood spots through the house came from a wound and that the murder weapon was likely to have been a flashlight.

Kirk wrote a 19-page report that he gave to Corrigan in 1955. Corrigan cited the findings in an appeal but was turned down by the Ohio Appeals Court that criticized Kirk’s conclusions as “highly speculative and fallacious.”

In 1956, Karl Schuele, who lived next door to the Sheppard’s empty house, discovered a corroded flashlight in the shallow waters of Lake Erie. He turned it in to Bay Village Police Chief John Eaton. According to Neff, “Eaton filed a report, noting that the flashlight was dented and battered at one end as if someone had used it for ‘striking something repeatedly.’” Neff reports that no one in the coroner’s office examined it for trace evidence.

The Triumph of F. Lee Bailey

For years, Corrigan filed appeal after appeal, all of which were turned down. In 1961, Corrigan died. However, there was a bright spot that year for Sam: the publication of The Sheppard Murder Case by Paul Holmes, a book that argued for Sam’s innocence. An ambitious young attorney named Francis Lee Bailey, who would become famous with his first name abbreviated to its first letter, read the book and wanted to defend Sam. Bailey soon started work on the case that would catapult him to glory.

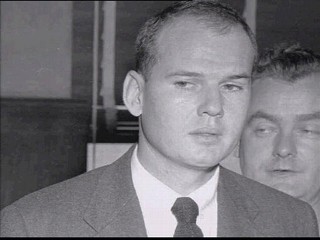

|

|

| F. Lee Bailey |

Bailey believed he worked in a more favorable environment than Corrigan had because the U.S. Supreme Court was then headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and was starting to dramatically expand the rights of the accused.

Bailey went before Federal District Judge Carl Weinman with a long list of wrongs. Neff reports that the following were among them: “Dr. Sheppard was arraigned without his lawyer, despite asking for a short delay so he [the lawyer] could arrive. The trial judge refused to move the trail to another city despite venomous pretrial publicity. . . . Detectives testified repeatedly about Sheppard’s refusal to take a lie detector test. In violation of Ohio law and without the judge’s permission, jurors, while deliberating, were allowed to make unmonitored telephone calls.”

In March 1964, Bailey was a guest at a discussion with columnist Dorothy Kilgallen. Kilgallen stated that, prior to the trial, Judge Blythin had told her Sam was “guilty as hell.” She said she had not originally reported this because it had been said to her “in confidence.” Bailey had something to add to the list of Sam’s legal grievances.

On July 15, 1964, Judge Weinman overturned Sam’s conviction, blasting the 1954 trial as a “mockery of justice.” Neff writes that Weinman cited five reasons for overturning the verdict, each one sufficient by itself to require a new trial: Judge Blythin’s failure to disqualify himself after making biased remarks about the case; Blythin’s failure to move the trial to another city; allowing detectives to testify that Sheppard refused to take a lie detector test; letting jurors make unsupervised phone calls in the middle of their deliberations; and Blythin’s failure to shield jurors from slanted news coverage.”

Sam was released from prison. Within days of his release, he wed Ariana Tebbenjohanns, a woman with whom he had pursued a romance through the mails.

On March 4, 1965, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Cincinnati overturned Judge Weinman’s reversal. Sam remained free on bail while Bailey appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In front of the Supreme Court, Bailey argued that Sam “was so thoroughly tried and convicted by the news media that a fair trial in the courtroom could not and in fact did not occur.” Bailey also pointed to Kilgallen’s deposition in which Judge Blythin told her prior to the trial that Sam “was guilty as hell.”

On June 6, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Sam’s conviction and ordered that he be retried or released. In the majority opinion, Associate Justice Tom Clark wrote that “virulent publicity” had violated Sam’s right to a fair trial and that Judge Blythin had not properly warned the jury against getting information about the case from sources outside the trial.

The Second Trial

The lead prosecutor at the second trial was Cuyahoga County Prosecutor John T. Corrigan. His co-counsel was Prosecutor Leo Spellacy.

The presiding judge was Francis J. Talty. He ordered the jurors sequestered and calls to their families monitored.

Russ Sherman was Bailey’s co-counsel.

In a bold move, Bailey told the jury that they would not only hear evidence suggesting Sam was innocent but learn of a plausible alternative killer. Bailey intended to put forth a theory first proposed in Holmes’s book.

Holmes’s theory was as follows: Marilyn had been having an affair with a man who lived close by and was also married. Her lover saw the house dark except for a light in the dressing room and took this as a signal that Sam was gone. He snuck into the house and did not see Sam sound asleep on the daybed. The man’s wife was alarmed by his absence but figured out where he was. The jealous wife came into the house and attacked Marilyn. Sam woke to Marilyn’s screams and was later knocked unconscious twice by the man who had decided to aid the wife he had betrayed. The man staged a burglary.

Holmes named neither villain nor villainess in his book but anyone familiar with the case knew he meant Spencer and Esther Houk.

In Bailey’s opening, he stated that the killer’s “physical strength was compatible with that of a woman.”

Dr. Lester Adelson took the stand and detailed Marilyn’s wounds. Under Bailey’s cross-examination, Adelson said it was possible that Marilyn’s teeth were broken by being pulled from inside. Bailey wanted to suggest that the bitten killer had a flowing wound that Sam did not.

The prosecution called Spen Houk. He testified to Sam’s morning phone call.

When Bailey cross-examined Spen, Bailey brought out that the Houks had not called the police after Sam called nor had they brought a weapon to the residence. Bailey asked if they had any reason to believe the killer was gone and Spencer answered, “I just didn’t give it any thought.”

Bailey asked Spen if he remembered a Spang Bakery driver at the Sheppard residence. Spencer replied, “Quite possibly.” He also elicited from Spen the statement that he had once brought a meal to Marilyn when she was sick in bed.

Esther Houk testified to seeing Marilyn’s bloody corpse. Questioned by Bailey, she testified that she had started a fire in her living room fireplace that morning. Neff writes that Bailey “hoped to suggest that the fire may have been used to burn evidence such as bloody clothing.”

Gerber testified to finding Sam’s watch in the green bag in the bushes and to the bloodstains on Marilyn’s pillow. When the prosecution questioned him, he refrained from speculating as to what the weapon was.

Bailey eagerly cross-examined Gerber on this point and that cross is recounted in The Defense Never Rests by F. Lee Bailey with Harvey Aronson.

Gerber: It looked like a surgical instrument to me.

Bailey: Just what kind of surgical instrument do you see here?

Gerber: I’m not sure.

Bailey: Would it be an instrument you yourself have handled?

Gerber: I don’t know if I’ve handled one or not.

Bailey: Do you have such an instrument back at your office?

Gerber: Shakes head.

Bailey: Have you ever seen such an instrument in any hospital, or medical supply catalogue, or anywhere else, Dr. Gerber?”

Gerber: No, not that I can remember.”

Bailey: Tell the jury, doctor, where you have searched for the instrument during the last 12 years.

Gerber: I have looked all over the United States.

Bailey: By all means, tell us what you found.

Gerber: I didn’t find one.

The prosecution called Mary Cowan. She testified that Sam’s watch had blood spatter on it. The implication was that it was spattered while Sam wore it while he beat Marilyn.

Bailey asked her if she had examined a rivet hole on a broken link of the watch’s band for blood. He was suggesting that blood inside it would mean it got there after it was broken.

Cowan conceded she had not.

Bailey called Jack Krakan to the stand. He had delivered bread to the Sheppards for Spang Bakery. He testified to seeing Marilyn kiss a man and to walking in as Marilyn handed the man a key and said, “Don’t tell Sam.”

Kirk testified that the blood spatter pattern indicated a left-handed swing. Sam was right-handed. He also testified that although the unique bloodstain was type O, as was Marilyn’s, it probably came from a different person because there was a difference in the rate of agglutination, or clumping, between it and the other spots.

Bailey asked Kirk about the blood on Sam’s watch. “For the most part it looks like contact transfer,” Kirk testified. As Neff observes, the implication was that a bloody “someone or something” had “pressed against the watch.” Kirk continued that a spot on the blood did not have the “symmetrical tail” characteristic of flying blood.

Bailey called Richard Eberling to the stand. Eberling once owned Dick’s Window Cleaning Service and had regularly washed windows for the Sheppards.

Eberling said he had told police a few years after the murder, when he was arrested for stealing, that he had cut his hand and bled in the Sheppard home.

Bailey did not call Sam to testify. In The Defense Never Rests, he writes that this was because Sam had turned to “booze and pills” to cope and was often “unaware of what was going on around him.”

Prosecutors called chemist Roger Marsters to the stand as a rebuttal witness. He supported Cowan’s assertion that flying blood had gotten on Sam’s watch.

On cross-examination, Bailey asked if Marsters had examined the watch to find out if it had blood in areas that would not have been exposed when the watch was worn. Marsters said he had not.

Bailey directed Marsters’s attention to a projected image of the watch. Neff writes, “He directed Marsters to the gap between the rim at the number 12 and the pin anchoring the first link of the band. Everyone in the courtroom could easily see through the gap to the inside of the band, the surface against the skin. Staring back like a pair of dull, far-set eyes were two small rust-colored spots that resembled other tiny spots that Mary Cown said were flying blood. Bailey’s point was obvious to all even before he asked the next question: It was impossible for a watch worn on the wrist to be spattered on the inside of its band. Did you ever notice the blood spots on the inside of the band?”

Marsters answered, “No, I honestly can’t say that I did.”

The case went to the jury on the morning of November 16, 1966. They had a verdict that same day: not guilty.

After Sam’s release, a book he had written in prison, Endure and Conquer, shot to the best sellers list. However, much of the profits went to pay Bailey’s fees. Sam was re-instated as a surgeon but his skills had deteriorated due to lack of use and alcoholism. Twice he was sued for malpractice due to patient deaths. He and Ariana divorced after four years of marriage.

Sam eventually had a new career as a wrestler with the moniker “Killer Sheppard.” He married the daughter of his manager, 20-year-old Coleen Strickland. On April 6, 1970, Sam died at 46 of Wernicke’s acute hemorrhagic encephalopathy, a liver illness that often strikes alcoholics.

The Sam Sheppard case may have been immortalized in the TV series “The Fugitive” that started running in 1963. Although series makers always denied the connection, the parallels between its plot and Sam were glaring. In the show, David Janssen plays Richard Kimble, a Midwestern physician unjustly convicted of the murder of his wife. Kimble had left the house after an argument with his wife. When returning, he saw a one-armed man running away – then found his wife beaten to death. Convicted of the crime, Kimble was sentenced to death. The train taking him to the execution is derailed and Kimble escapes. He chases the mysterious one-armed man and police officers, most prominent among them Lieutenant Phillip Gerard (Barry Morse), chase Kimble. There is often conflict as Dr. Kimble must risk getting caught in order to treat someone injured or sick. The program possessed a great deal of dramatic tension for, as Neff notes, it was “a cop show, a doctor show, and a chase show all in one.” It was probably more than coincidence that the show aired its last episode – one in which Kimble and Gerard join forces to chase the one-armed man and Kimble is vindicated and set free – about a year after Sam’s acquittal

Sam Reese Sheppard’s Crusade

When Chip Sheppard grew up, he shed his nickname and determined to vindicate his father. Sam Reese’s interest was piqued in late 1989, when Richard Eberling was convicted of murder.

Sam Reese and others wondered if Eberling had been involved in Marilyn’s death. In 1960 Eberling was convicted for a series of thefts. The window washer had taken cash, jewelry and figurines from homes in which he worked. He often took gems from their setting and sold them. However, he had kept two rings intact: those of Marilyn Sheppard. He had not stolen them from the home she shared with Sam but from a box labeled “Personal Property of Marilyn Sheppard” in the home of Dr. Richard Sheppard. When questioned, he said he did not know why he kept Marilyn’s rings. He also told police he had cut his hand at the Sheppard residence a few days before the murders and dripped blood through the house.

The murder for which Eberling was imprisoned had originally been identified as an accident. He had worked as a caregiver for the elderly Ethel Durkin. Her 1983 death was initially recorded as the result of an accidental fall. In 1987, a woman who had partnered with Eberling in a fraud scheme reported to police that Eberling had murdered Durkin after forging a will giving him most of her estate. Her body was exhumed and autopsied, showing that she had been struck on the head and neck.

An amateur detective who used the moniker “Monsignor” phoned Sam Reese to inform him that Eberling had a story to tell Sam Reese. Sam Reese wrote to Eberling who wrote back indicating he knew the true story of Marilyn’s murder. Eberling claimed, “Her death was not intentional” and “The pressure build-up caused temporary insanity.” Sam Reese assumed Eberling was referring to himself.

Sam Reese visited Eberling at the Lebanon Correctional Institute. Neff writes that Eberling recalled being in the Sheppard house two days before Marilyn’s murder and hearing Esther Houk scream at Marilyn, “I will kill you if you don’t leave my husband alone.”

In 1995, Reese filed a lawsuit against the state of Ohio, on behalf of Sam Sheppard’s estate, for Sam’s “wrongful imprisonment.” Sam Reese asked for $2 million, one third of which would have gone to his attorneys.

While Sam Reese waited for the case to be heard, Eberling died in prison of a heart attack.

Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court Judge Ronald Suster presided at this civil suit. Terry Gilbert was lead attorney for plaintiff Sam Reese. George Carr was Gilbert’s co-counsel. William D. Mason was lead attorney for the defendant, the state of Ohio. His co-counsel was Steve Dever. Assisting them were Dean Boland and Kathleen Martin.

Opening statements were made February 14, 2000 and the case went to the jury in April.

They reached their verdict within hours: the plaintiff, Sam Reese Sheppard, had not proven that his father had suffered wrongful imprisonment.

Sam Reese appealed and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eight District ruled in February 2002 that the case should never have even been heard in the first place as a claim for wrongful imprisonment could only be brought by the individual who had been imprisoned

While the Sam Sheppard case appears to have reached its end as a legal matter, it continues to haunt the culture.

One of the things that has kept the Marilyn Sheppard murder alive in the annals of true crime is that the case has an extraordinary line-up of plausible suspects without any of them being proven to have committed the crime.

What about Esther and Spencer Houk?

The Houks had not called the police after Sam phoned them with the message that Marilyn had been killed. They headed over to the Sheppard residence without bringing a weapon even though they had no way of knowing that a murderer was not still there. When they got there, Esther ran up to the bedroom in which Marilyn had been killed without being told where Marilyn was. The Houks did not attend Marilyn’s funeral.

Spen was hospitalized with a nervous breakdown a few weeks after Marilyn’s death.

F. Lee Bailey and Paul Holmes both subscribed to the belief that Esther killed Marilyn because Spen had a tryst with Marilyn and that Spen got into a fight with Sam in order to cover up for Esther.

In 1989, Sam Reese received a letter from the imprisoned Richard Eberling in which Eberling claimed to know “the entire story.” The two began corresponding and Sam Reese started visiting Eberling in prison. The journalist working with Sam Reese, Cynthia Cooper, also visited Eberling. Eberling also fingered Esther but his scenario was different.

Eberling said he had been washing windows at the Sheppard home two days before the murder. Spen came over while Sam was still there with Marilyn. Spen stayed after Sam left. After Spen left Esther came over. Eberling was not in the room with the women but heard Esther scream, “If you don’t leave him alone, I’ll kill you!”

Later Eberling said he knew another secret: Spen had been having a homosexual affair with Sam. Eberling claimed to have learned this through an employee who had been washing windows at a hotel in which the two men enjoyed a rendezvous. Eberling believed Esther had been mad at Marilyn thinking Spen was having sex with the wife when he was actually having sex with the husband.

Eberling claimed to have run into Sam shortly after Sam’s acquittal and that Sam had confided the following story. On the murder night, Spen went to Sam’s for a tryst. Esther, thinking Spen was going to see Marilyn, followed. Esther went upstairs and attacked Marilyn. After her rage was spent, she claimed to have gone crazy. Sam felt sorry for her and agreed to help Spen stage a cover-up. Sam assumed his story of the “bushy-haired man” would be believed and felt stuck with the lies he had agreed to even after being wrongly convicted.

However, it seems odd that Sam would not have come clean during the decade he was imprisoned.

Did Sam really do it?

There is also the possibility that Dr. Sam really was guilty as charged. DeSario and Mason argue for this position in Dr. Sam Sheppard on Trial. The dust jacket of their book has the words “case closed” on it although they are probably optimistic to believe that everyone will accept their version of events. However, they spiritedly defend the original investigators and prosecutors.

They do not pretend to know the precise motive. The idea that Dr. Sam planned to kill his wife so he would be free to marry another woman without the stigma attached to divorce in the 1950s seems far-fetched. After all, he disregarded the stigma attached to open philandering. It would seem more likely that he erupted in rage during a heated argument. That could have occurred because Marilyn took him to task for his infidelity.

It is also possible that Sam was infuriated because Marilyn confided that her pregnancy may have been sired by another man. That scenario also seems weak because of the timing of the pregnancy.

It also leaves us with the puzzle of the broken sports trophies. Sam would be unlikely to destroy the sports trophy he cherished. Of course, it is possible that he might do so as part of a staged scene but that opens the question of why other items were not randomly destroyed. Another possibility is that he and Marilyn initially got into an argument downstairs and that each smashed the other’s trophy.

Richard Eberling: Window washer turned millionaire turned murderer

James Neff, Sam Reese Sheppard, and Cynthia Cooper all point fingers at Richard Eberling as Marilyn’s probable murderer. Both The Wrong Man and Mockery of Justice devote a great deal of space to the singular odyssey of the orphan turned window- washer turned millionaire turned convicted murderer.

Richard Eberling was born Richard Lenardic to Louise Lenardic, an unmarried 19-year-old Yugoslavian immigrant. His paternity was never established. Louise could not care for him but would not sign him over for adoption. Soon after his birth, Richard began shuffling between foster homes. Cooper and Sheppard write that the boy was in five different homes before he reached 7. A fussy baby, he had temper tantrums and blackouts.

When of school age, he stole, lied, wet his bed, and engaged in sex play with other boys. He got in trouble at a new school for forcing kisses on girls.

As an adult, Richard claimed that when he was 7 a foster father raped him.

However, he was industrious in an unexpected manner: He loved cleaning houses and arranging furniture.

At eight, Richard was placed as a foster child with the farm family of George and Christine Eberling. Richard got along well there although he often stole small items from the Eberlings and their acquaintances.

George Eberling died in 1946. By then, Richard was a teenager. He wanted to participate in sports. Christine forbade him to because she insisted he needed to work at home and feared his getting injured.

Christine told Richard he should become a doctor. He liked this idea but his low grades made it impractical.

Although never adopted by the Eberlings, Richard persuaded a court to change his name to Richard George Eberling. As a young adult, he began a window-washing business.

Eberling’s life often appeared plagued by accidents. In 1955, a fire destroyed Christine Eberling’s barn shortly after he arrived home. Some Eberlings griped that a disproportionate amount of the insurance payoff went to Richard because of furniture he had stored in the barn.

In 1956, Richard crashed his car into a parked truck and his date was killed. An autopsy determined that the death was an accident.

In 1960, Eberling met Oscar B. “Obie” Henderson. The two men were instant friends. They were soon housemates, a relationship that would last 30 years. They stoutly denied being gay but friends spoke of them as a couple.

Around the same time, Eberling began working for Ethel May Durkin. He and the elderly, childless, affluent widow hit it off immediately. He was soon doing odd jobs around her home and keeping her company. His presence did not sit well with Ethel’s sister, Myrtle Fray. Once when Eberling was in another room of Ethel’s home, Myrtle berated her sister, saying, “You’ve got to get rid of him. He’s a crook.” Ethel retorted, “He’s over all that.” They continued arguing and Ethel pointed out that Richard could hear Myrtle who answered, “I don’t care if he hears me or not!”

Myrtle was murdered in 1962. She was found with her face beaten and her body exposed because her nightgown had been ripped open. Apparently no effort was made to test for semen.

Years later, Richard would say he had a theory about the murder. “It had to be a woman,” he said. He believed this because he thought it would be difficult for a man to leave her apartment without being spotted by the neighbors. However, he speculated that if a man killed Myrtle, he had dressed in women’s clothes.

Myrtle’s Fray’s murder was never solved.

In 1970, another Durkin sister, Belle, who lived with Ethel, fell down a flight of stairs and died a few months later.

The 1970s appeared to be good years for Dick’s Window Cleaning that now included putting up screens and storms and doing some interior decorating. The company was renamed R. G. Eberling & Associates. In 1972 Cleveland Mayor Ralph Perk hired Richard to remodel the mayor’s office. The job finished in 1976. According to Cooper and Sheppard, it “was declared an aesthetic success.” However, the next mayor did not retain Richard’s services.

Eberling and Henderson were often seen about town, hobnobbing with the elite and in the company of single women. One of Eberling’s friends said, “He was always looking for old ladies to take care of. He’d be really nice to them. If you’d be nice to them, they’d be nice to you.”

After Eberling’s dismissal from city hall work, he spent increasing time with Ethel. Henderson as well as Eberling frequently kissed her and flirted with her. Henderson sometimes fixed her hair.

Cooper and Sheppard report, “From 1979 to 1982, Ethel suffered a series of falls.” She signed a power of attorney making Eberling’s longtime roommate, Obie Henderson, executor of her will. In November 1983, Ethel became disturbed when a caregiver resigned. Ethel persuaded the woman to return. Then Ethel called her before she was supposed to show up and said, “Richard says no.”

On November 15, 1983, Eberling phoned police to say medical personnel were needed. They found Ethel lying on the floor, breathing but unconscious. Eberling told them she had fallen. She was hospitalized, unable to speak, until she died on January 3, 1984.

Ethel’s will named Henderson as executor and left him 4 percent of her estate. Seventy percent of the $1.4 million estate was left to Eberling. The friends lived lavishly for several years.

In 1987, a woman contacted police claiming to know Ethel’s will was fraudulent and suspected foul play in Ethel’s death. She had been in cahoots with Eberling and had been one of the witnesses to the will.

Investigation revealed that the will had been typed after it had been signed. Eberling persuaded Ethel to sign a blank sheet of paper by telling her he wanted to have her handwriting analyzed. Ethel’s body was exhumed and the coroner found that she had died from blows to the back of her head and face.

Henderson went to prison for several years for fraud and theft. Eberling was convicted of similar crimes and also of Ethel’s murder. Claiming innocence, he died in prison.

There are many reasons Cooper, Sheppard, and Neff pin Marilyn’s murder on Richard. Having worked at the home regularly, he was intimately familiar with it. A large man, he might have been able to defeat a confused Sam in a physical fight. If the jury in the Ethel Durkin murder decided correctly, Eberling was capable of murder. Moreover, the beating death of Ethel resembled the beating death of Marilyn. Although he was only charged with one murder, the string of mysterious deaths in his wake lead some people to suspect he was a multiple murderer.

Cooper and Sheppard note, “Eberling, who was ever conscious of money, did not present the information that he later claimed to have when a $10,000 reward was offered by the Sheppard family.”

If he were the murderer, puzzling aspects of the case would make sense. He might have smashed sports trophies because of his long simmering frustration at his having been denied a chance to go out for sports in high school. Turning over Sam’s medical bag may have grown out of his regret at not being able to fulfill his foster mother’s dream for him of becoming a doctor. Even the neat pulling out of drawers makes sense in light of Richard’s penchant for tidiness.

Then there is the strange story he told of his having dripped blood in the house just days before the murders. It had not been suggested that Eberling’s blood was in the house so why would he try to account for its presence? In 1990, Vern Lund, a dying man who had once worked for Dick’s Window Cleaning, contacted Sam Reese, to say that he, not his boss, had worked in the Sheppard home days before the murder.

Over the years, Eberling made several comments about Marilyn. Asked if he might have dated her if he had met her before Sam, he answered, “Probably not. I was an orphan, she was a golden girl. . . . I wasn’t good enough.” He said, “She was a lovely lady. . . . I think she was lonesome because she let a lot of family dirt out to me.” Neff quotes him saying that she wore, “Tight little brief shorts and a very little blouse. She was immaculate, all in white.” Neff also reports that Richard said Marilyn hospitably invited him to enjoy milk and brownies with her and Chip. Neff comments, “He was describing an ideal mom – feeding him comfort food.” Eberling describes Marilyn as both an idealized mother and a sexual tease: a particularly alarming combination considering his history of abandonment by mother-figures and possible sexual confusion.

DeSario and Mason show a photograph of Richard Eberling, already balding in 1954, and pointedly ask, “Is this the bushy-haired man?” However, Cooper and Sheppard report, “He wore toupees and ones that, by the account of a friend, gave him a ‘bushy-haired’ appearance in 1954.”

However, there is no evidence conclusively proving Eberling was in the Sheppard house on the night in question.

The Marilyn Sheppard murder remains officially unsolved. With its line-up of suspects both colorful and plausible, it is a tantalizing mystery.

Bibliography

Bailey, F. Lee with Aronson, Harvey, The Defense Never Rests, Stein and Day, New York, 1971.

Bailey, F. Lee with Rabe, Jean, When the Husband is the Suspect: From Sam Sheppard to Scott Peterson – The Public’s Passion for Spousal Homicides, A Tom Doherty Associates Book, New York, 2008.

Conners, Bernard F., Tailspin: The Strange Case of Major Call, British American Publishing, Ltd., Latham, New York, 2002.

Cooper, Cynthia L., and Sheppard, Sam Reese, Mockery of Justice: The True Story of the Sheppard Murder Case, Northeastern University Press, Boston, 1995.

DeSario, Jack P. and Mason, William D., Dr. Sam Sheppard on Trial: The Prosecutors and the Marilyn Sheppard Murder, The Kent State University Press, Kent and London, 2003.

Neff, James, The Wrong Man: The Final Verdict on the Dr. Sam Sheppard Murder Case, Random House, New York, 2001.