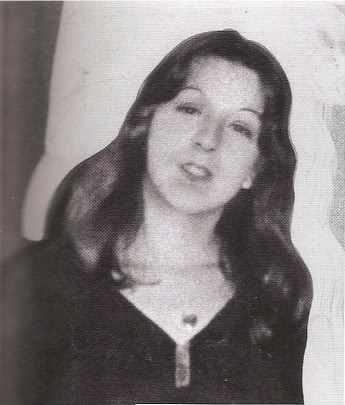

Joan Webster

On Saturday November 28, 1981, Joan Webster, a 25-year-old Harvard graduate student, landed at Logan Airport in Boston aboard Eastern flight #960. Shortly after retrieving a suitcase from the luggage carousel, she disappeared.

by Eve Carson

Joan Webster, a 25-year-old, second-year student at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, had everything going for her as she flew back to Boston after spending Thanksgiving with her parents in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. Just before she took the holiday break, her presentation of an 11-week auditorium project had been rewarded with high accolades from her teacher and classmates.

At Harvard, she was the dorm proctor at Perkins Hall. Smart, popular, attractive, she was available to anyone who needed her help and friendship. A quote tacked on her dorm room wall read, “It costs so much to be a full human being.”

Her flight aboard Eastern # 960 and several other flights arrived at Logan Airport around 10 p.m. on Saturday, November 28, 1981. As Joan went to retrieve her one stowed suitcase, many passengers crowded around the only luggage carousel in use that night. Shortly after retrieving her suitcase, Joan Webster disappeared.

In the days following her disappearance, the media continuously reported that Joan simply vanished after waiving to a friend at the airport. Many years later when I took up in earnest trying to find out what really happened to Joan, who was my sister-in-law, I recovered documents that revealed that a cab driver believed he saw her as she left the airport. Lt. Larry Murphy, of the Harvard Police, told the Boston Globe that the cabbie provided a composite description of a bearded man believed seen leaving the airport with Joan. Strangely, authorities suppressed the image and it was never broadcast to the public.

Joan arrived at Logan Airport wearing a red print blouse, black skirt, navy blue scarf, a brown Chesterfield coat, and brown knee-high leather boots. She was carrying a red purse, a tote bag, and a navy blue Lark suitcase. The purse was found in a known dumping ground, a marshy area along both sides of Route 107 in Saugus, Massachusetts on December 2, 1981, four days after her disappearance. A sum of less than $100 was missing, but her credit cards and checkbook were in the bag. It was reported later that a distinctive gold charm bracelet was missing from her purse, but that was not publicly known at the time. An extensive search produced no other clues in the area. The location was on the south side of the Lynn Marsh Road, seven miles north of the airport, and in the opposite direction from Cambridge where Joan resided at Perkins Hall.

Joan’s suitcase was recovered intact and undisturbed on January 29, 1982, in a Greyhound Bus terminal. The media reported it was recovered in the Park Square Station in downtown Boston. As would prove to be typical about so many details involving Joan’s disappearance, the Boston Herald revealed in 1990 that the bag may actually have been discovered in New York.

The tote bag Joan carried was never located. Reports described its contents: pamphlets, books, records, and shoes. Fragile architectural drawings were also contained in the carry-on, but that item was not disclosed to the public.

Joan’s disappearance was initially handled by the Middlesex County D.A.'s office of John Droney, the office that covered Cambridge, Massachusetts. Assistant D.A. Carol Ball was assigned to the case in December 1981 with the Massachusetts State Police Crime Prevention and Control unit assigned to that office. The office handled the case for several months and followed numerous leads to dead ends. A legal assistant working in that office on Joan’s case affirmed that the composite drawing constructed in December of 1981, the likeness of a bearded man believed seen leaving the airport with Joan, was never provided to the Middlesex D.A.’s office.

Middlesex pursued another hypothesis, a claim made by a California Mensa theorist who was studying the Zodiac murders a decade before in California. Gareth Penn calculations implicated a Harvard professor, Michael Henry O'Hare, as the serial killer who ended his spree with Joan Webster. Penn contacted Joan’s parents and gave them a 119-page manifesto outlining his theory. The calculations were turned over to the Middlesex office and the FBI, and the investigation was diverted down another dead end. Penn published his theory in 1987 in Times 17, and detailed his extensive contact with the Webster family. The FBI dismissed his theory as one with forced conclusions that lacked a concrete foundation of proof.

The Murder of Marie Iannuzzi

|

| Marie Iannuzzi |

Marie Iannuzzi was murdered in 1979. She was strangled and dumped on the rocks by the Pine River. The area was a known dumping ground on the northbound side of Route 107 behind a vacated business. The victim was found wearing a red, one-piece bodysuit with no snaps in the crotch, a matching wrap around skirt, and a black scarf double knotted tightly around her neck. She was not wearing her shoes and stockings. Her clothes were intact, and no jewelry was missing. Police ruled out rape and robbery as motives for the crime. A prime suspect in Marie’s murder was her boyfriend, David Doyle, an unemployed drug user with a known violent relationship with Marie Iannuzzi.

In February 1981, the Iannuzzi case was reassigned to Trooper Andrew Palombo, a bearded undercover cop who worked with informants, and who was based out of F Barracks at Boston’s Logan Airport. The case was still handled by prosecutors in Essex County, but Trooper Carl Sjoberg was usurped. One of the informants who reported what he heard on the streets to Palombo was the prime suspect in the Iannuzzi case, David Doyle.

The Iannuzzi case had gone cold and the high-profile disappearance of Joan Webster was going nowhere until January of 1982 when a woman placed two anonymous calls. One call linked a man named Leonard Paradiso, a parolee, to the 1979 murder of Marie Iannuzzi and the other call linked Paradiso to Joan’s disappearance. The first call was to the Saugus police, the second was to the parents of Joan Webster.

In the call to the police the woman claimed to have been assaulted by Paradiso in 1972, and she said he was responsible for Marie Iannuzzi’s murder. In the call to Joan’s parents, she told them she was basing her accusations against Paradiso on her alleged 1972 assault. The woman, later identified in court records as Patty Bono, was from the North End of Boston and knew Leonard Paradiso growing up. She also had another childhood acquaintance from the North End, Sgt. Carmen Tammaro of the Massachusetts State Police assigned to F Barracks at Logan Airport—Trooper Palombo's superior officer.

|

| Trooper Andrew Palombo |

For David Doyle the calls placed by Patty Bono were a godsend. Instead of the police investigation focusing on his known abusive relationship with Marie Iannuzzi, it would now veer off in Paradiso’s direction with a vengeance. How Doyle escaped prosecution for Marie’s murder is a mystery onto itself.

The day before boaters found Marie’s strangled body, she and Doyle had fought in front of numerous witnesses during Doyle’s cousin's wedding reception. On this particular day, it was verbal, but his mother had to take his arm and get him out of the reception. The couple was known to have physical fights though, something Doyle admitted himself.

Two months before her murder, Marie Iannuzzi had gone to stay with a friend, Christine DeLisi, claiming Doyle had tried to kill her. Multiple witnesses corroborated the strangulation marks on Marie’s neck. Doyle knew his girlfriend was seeing another man, Eddy Fisher, and she had been with the other man the night before Doyle and Marie attended the wedding reception. After that weekend, family members reported to police they saw deep gauges on Doyle's hands and observed blood on the steps up to the couple's apartment on the top floor of his parent's home.

Autopsy photos showed Marie's long manicured nails in a clawed position, but incredibly no scrapings were taken. Stepsister Jean Day reported she saw Marie's belongings packed early Monday morning, before family members identified the body, in the apartment Doyle shared with Marie. According to numerous witnesses, Doyle was noticeably strung out during the wake, and he took flight before the funeral. The victim’s boyfriend was arrested stealing from suitcases on the luggage carousel at Newark Airport in New Jersey, and he had a stolen airline ticket from Newark to LaGuardia in his possession.

Leonard Paradiso attended the same wedding with his girlfriend, Candy Weyant. At the request of the groom’s father, Candy gave Marie a ride to a bar two blocks from the apartment she shared with her boyfriend, David Doyle. When Paradiso and Weyant later found items in Candy’s car they presumed were Marie's, they detoured from their drive home to return them to Marie at the bar. Paradiso held the door for Marie as she exited about one o’clock in the morning and turned to tell a friend she would be back in half an hour. Candy waited in the car while Paradiso returned belongings to Marie in the bar, and both told police they watched Marie walk around a corner and never saw her again.

Marie’s friend in the bar, Christine DeLisi, did not wait to see if she returned, and the state began promoting the supposition that Paradiso was the last person seen with the victim alive.

The Websters’ Involvement

Both of Joan’s parents, George and Eleanor Webster, worked for the CIA when they met; their unique background added individuals who were trained in intelligence to the complex search. The Websters would play a major role into the investigation of Joan’s disappearance as would the conglomerate George Webster worked for at the time as a senior executive: ITT.

At the time of Joan’s disappearance, ITT was still reeling from two major scandals that rocked the company in the 1970s. One involved Watergate plumber, and former CIA operative, E. Howard Hunt. Hunt was instrumental in discrediting a memo from ITT lobbyist Dita Beard who documented the financial influence ITT held over Richard Nixon's White House. Company CEO Harold Geneen funded Nixon’s reelection coffers substantially in return for a favorable resolution to an anti-trust suit levied by the U.S. Department of Justice against the corporation. E. Howard Hunt was enlisted to discredit Dita Beard’s memo that exposed the favor.

The second scandal hit a bit closer to home for George Webster. His position at ITT was the director of budget and planning for the Defense Group in the telecommunications division. His division had acted as a cover firm for the CIA for more than a decade in efforts to undermine the politics in Chile and save ITT’s interest in Chitelco, Chile’s telephone company. The U.S. Department of Defense controlled 80 percent of the intelligence budget, and was the chief consumer of the intelligence product. This put George Webster in the position to straddle interests of his current and his former employer. Efforts in Chile ended disastrously, and brutal dictator Augusto Pinochet rose to power.

The Senate Church Committee commenced in 1975 and continued through 1977. Senators scrutinized the CIA and ITT for misconduct, but participants were shielded from accountability. Just a few years after the Senate concluded its inquiry, Joan Webster mysteriously vanished from Logan Airport.

The Investigation into Joan’s Disappearance

Just over two months after their daughter’s disappearance, the Websters requested a meeting with authorities. The meeting was held at Harvard and assembled an unprecedented and unwieldy list of participants. Middlesex County was handling Joan's disappearance; Essex County had jurisdiction where the purse was recovered (and it had jurisdiction of the cold Iannuzzi case), and Suffolk County had jurisdiction over Logan Airport where Joan disappeared. Lt. Col. John O'Donovan, in charge of the Massachusetts State Police, was in attendance with MSP officers representing the three D.A.'s offices and detectives from F Barracks at Logan Airport. The Saugus police and Harvard Campus police rounded out the impressive recruitment of resources for a missing person's case.

|

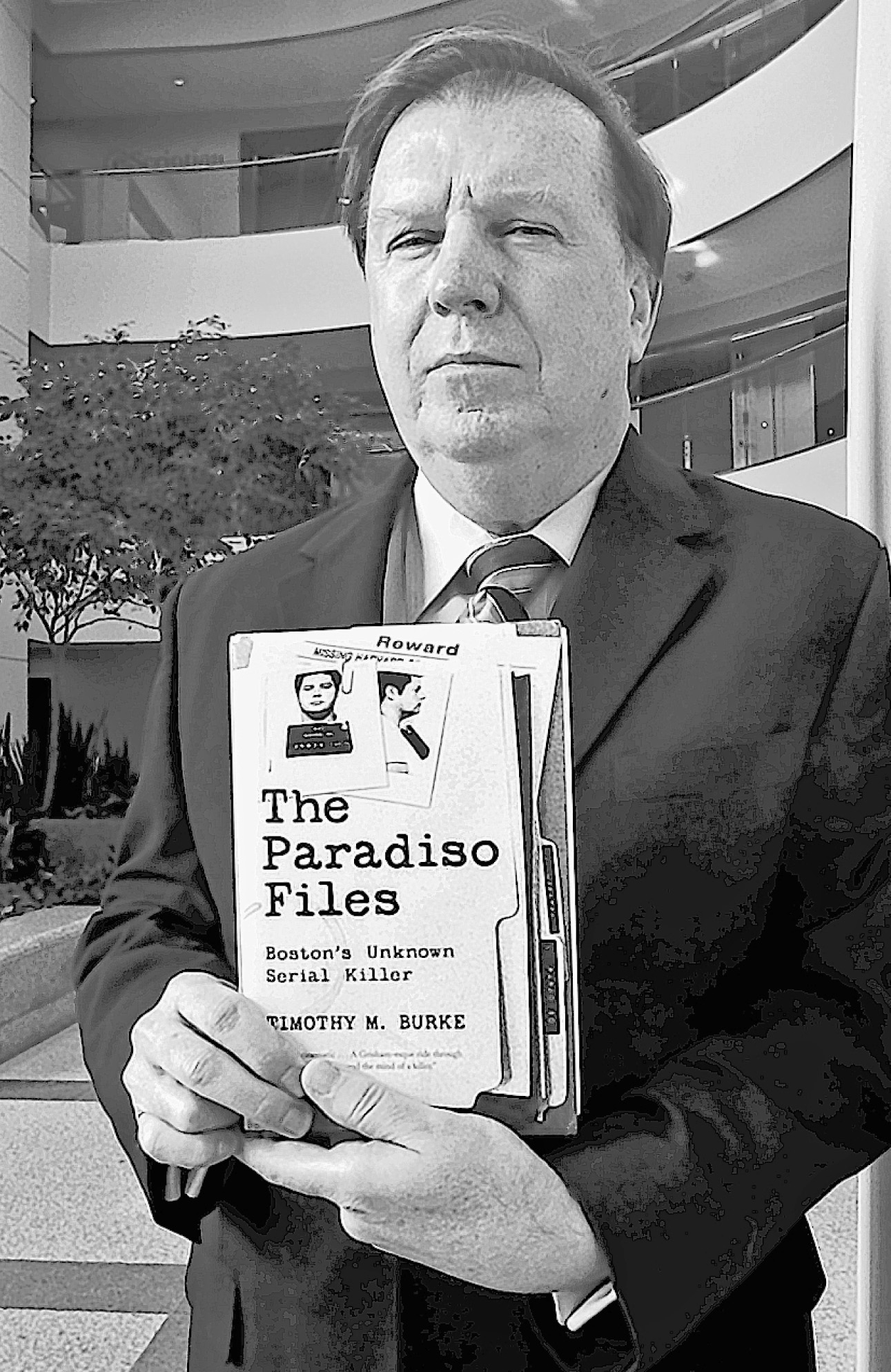

| Suffolk County Assistant D.A. Tim Burke |

The focus of the meeting was ostensibly Joan Webster, but the strategy that emerged from the meeting was unclear until 2008 when I began uncovering documents. I retained a private investigator and attorney in Boston in 2008 to help recover records and interview individuals connected to the Joan Webster investigation. I submitted Freedom of Information requests (FOIA) to recover FBI documents.

Although Middlesex County continued to pursue dead-end leads, and was the visible presence to the public on Joan's case, one of the upshots of the meeting was to shift the investigation to Suffolk County Assistant D.A. Tim Burke and Trooper Andrew Palombo of F Barracks at Logan Airport. Another upshot was to have Burke replace Essex County as the prosecutor in the Marie Iannuzzi murder case. This strategy gave the relatively novice assistant D.A. a clear shot at going after the named suspect from the anonymous calls: Leonard Paradiso.

Burke’s theory was that Paradiso was responsible for Iannuzzi’s murder and Joan’s fate and that he would be able to establish that by first convicting Paradiso of Marie’s death.

ADA Burke had only begun prosecuting murder cases in Suffolk County since the fall of 1981 when he took over the unresolved triple homicide case of Basilia Melendez and her two children.

On March 2, 1982, Burke issued subpoenas for a grand jury in the 1979 Iannuzzi case. The grand jury convened on Friday, March 5, 1982 in case #038655, the Commonwealth v. Leonard J. Paradiso, but testimony and strong circumstantial evidence brought out in the hearing implicated the victim’s boyfriend, David Doyle, for the crime. Tim Burke falsely asserted to the media and other enforcement agencies that this hearing was a John Doe grand jury. However, transcripts of the hearing clearly show that the Webster suspect, Leonard Paradiso, was the subject pursued.

On March 11, 1982, Trooper Carl Sjoberg was dispatched to meet with Paradiso's parole officer, Victor Anchukaitis, and Sjoberg implicated Paradiso in another Boston crime, later learned to be Joan Webster's disappearance. Later grand jury sessions, convened for the same case #038655, were renamed to John Doe grand juries. Paradiso was ultimately indicted for Marie’s murder on June 28, 1982 and a second indictment for rape was added on June 6, 1983, almost a full year later.

Using a Snitch to Close in on Paradiso

The supposed “break” in Joan's case came a year after the anonymous phone calls in January 1982 to the Saugus police, and the Websters naming Paradiso as a suspect. Paradiso was considered a suspect in Joan’s disappearance early in the investigation, before the grand jury hearings for the Iannuzzi murder began, but he was not identified to the public in Joan’s case until January 1983 after ADA Burke produced a snitch informant who claimed Paradiso had confessed to murdering Marie Iannuzzi and Joan Webster.

|

| Robert Bond |

Robert Bond was a twice-convicted murderer. Authorities moved him to the Charles Street Jail on December 8, 1982, for trial and positioned him close to Paradiso's cell. He was a known offender with a history of violent crimes against women. Bond gained a parole for the 1971 murder of Barbara Mitchell and pursued a relationship with Mary Foreman, a community activist he met while on a prison furlough. Numerous witnesses described Mary’s attempts to break off the relationship with Bond. He had physically assaulted her in August 1981, and harassed her; she was afraid of him. On October 23, 1981, he lured her to the house of one of his friends, a drug dealer, and shot her point blank through the temple. He was interviewed by the police on November 11, 1981, but lied to police and said he never saw Mary that night. The jury convicted Bond of Mary Foreman’s murder on December 13, 1982.

The convicted killer met with Sgt. Carmen Tammaro and the Massachusetts State Police on January 10, 1983, the same day the judge sentenced him to return to Walpole Prison. Strangely, instead of going back to the maximum-security lockup, Bond remained at the Charles Street Jail in close proximity to Leonard Paradiso until authorities moved him to a medium-security facility in Concord on December 29, 1982. This treatment of Bond is highly suggestive – sending a twice-convicted murderer to a medium-security prison – of his status as a government snitch.

Officers conducted a taped interview with Bond again on January 14. Trooper Palombo represented to the court in sworn warrants that this meeting was arranged based on an unsolicited letter ADA Burke received from Bond on January 5, 1983 detailing the murders of both Marie Iannuzzi and Joan Webster.

Transcripts of the meeting on January 14 exposed that the letter to Burke that authorities anticipated had not been received. In fact, Bond questioned an officer at Concord about the letter he sent three days before, mailed on January 10, 1983, a date when authorities met with Bond after his sentencing. The interview also revealed there were prior meetings with the Massachusetts State Police.

Bond was vague and confused on numerous points during the interview, and offered a multiple choice for Joan's murder. He initially asserted Paradiso strangled Joan, but then went over the scenario discussed in their prior meeting. He told officers they could decide. He did provide a clear order of events alleging Paradiso hit Joan in the head with a whiskey bottle, raped her, and dumped her in the ocean. Bond pointed to the right side of his head and described a lot of blood from the injury, but Joan's remains had not been discovered and would not be for another seven years. Tammaro, Palombo and Husdon were the three officers reviewing Bond’s affidavit the following Monday, January 17, 1983.

When Bond’s letter was finally produced it cleared up vagaries from the interview, but was false on numerous points. However, the letter did indicate Massachusetts State Police met with Paradiso three weeks after he was arrested for the Iannuzzi case, and police suggested Paradiso had murdered Joan on his boat. Another document corroborates a meeting Paradiso had with Sgt. Carmen Tammaro at that time. Tammaro initiated the boat theory on August 1, 1982, according to recovered documents. His assertions came four months before he led the interview with Bond and promoted a “break” in the case.

Bond claimed in his interview and his written affidavit that Paradiso hit Joan in the head with a whiskey bottle, raped her, and then took his boat way out and dumped her in the ocean. In sworn documents to the court, ADA Burke and Trooper Palombo reordered events stating Joan was raped first, and then hit in the head. Authorities maintained Bond’s assertion the body was discarded in the ocean. Bond saw photographs of Paradiso’s boat tacked up on the cell wall, and the inmate provided detail down to the registration number on the vessel.

Paradiso reported that his boat was missing on July 26, 1981, four months before Joan's fated disappearance, but authorities continued to promote Bond’s story, a theory that provided an explanation for not having a body. They also continued to implicate Paradiso for Marie Iannuzzi's murder, ignoring conflicting evidence already in the case files, evidence that pointed to her boyfriend as the assailant.

The first search warrant was finally issued on April 25, 1983 in the Iannuzzi case. It entangled Joan's investigation with Marie’s1979 murder, and sought and confiscated evidence related to Joan's case, not Marie’s.

To up the pressure on Paradiso, ADA Burke enlisted the Boston office of the FBI on May 3, 1983, and instigated bankruptcy fraud charges against Paradiso regarding the boat by contacting Special Agent Steve Broce in the personal Crimes Division of the Boston office. Paradiso had filed for bankruptcy on August 26, 1981, and did not list his boat or the insurance claim as an asset. The boat was the alleged crime scene for Joan’s murder. Burke endeavored to prove the boat was not stolen as claimed, but he did not establish his crime scene was above water when Joan disappeared. In fact, the Boston office of the FBI had been engaged in Joan's case since December 3, 1981, just days after her disappearance, but now multiple case numbers clouded the issue. (The state hid records in other files.)

In two different courtrooms, federal hearings ran in tandem with the state’s murder allegations in the Iannuzzi pre-trial, and the Feds listed Joan's name as a victim in the bankruptcy case in the FBI reports.This tied Joan Webster’s name to the boat.

Special Agent Broce of the FBI filed a search warrant for a safety deposit box held jointly by Paradiso and Candy Weyant, but found nothing related to the bankruptcy case or any crime. Regardless, Assistant U.S. Attorney Marie Buckley indicted Paradiso for allegedly lying on a bankruptcy filing. A confidential FBI report indicated that both offices, the Suffolk County D.A.’s office and the Boston office of the FBI, were working toward a desirable conclusion in the Iannuzzi and Webster cases. The FBI office could give the state additional investigatory resources.

Paradiso on Trial for Murder

|

| Leonard Paradiso on trial |

The participants in the Iannuzzi trial were the same people involved in Joan's investigation. The Iannuzzi trial began on July 9, 1984 against Leonard Paradiso. Key witnesses gave conflicted accounts from testimony they had given during the grand jury proceedings that began on March 5, 1982. During the grand jury, Marie's friend Christine DeLisi and her stepsister Jean Day both provided testimony that negated the state's assertions, and implicated the victim’s boyfriend, David Doyle, as the culprit.

Sworn affidavits have been recovered that these two witnesses said they had been threatened with prosecution (obstruction of justice) and never seeing their children again by members of the Massachusetts State Police and the prosecutor's office. Similar tactics were evident in the state's treatment of Paradiso's girlfriend, his alibi witness the night Marie was murdered. It was also evident in the pile-on tactics used against Paradiso himself; questionable witnesses came forward with unverified accusations against him for numerous crimes.

Dennis Slawsby, a private investigator working for the defense, also gave a sworn statement that he interviewed defense witness Jean Day in the courthouse on July 18, 1984, and that the answers she gave him were consistent with her grand jury testimony. She had been assaulted, and she had gone into hiding after the Bond allegations appeared in the paper. In his sworn statement, Slawsby stated that Day’s recollections were consistent with her grand jury testimony on March 5, 1982.

Judge Donahue held a side bar conference where Burke detailed the assault. The time frame was determined to be around the time the Bond allegations were circulated in the papers, January 1983. Burke claimed Day was asking questions about Paradiso at some bars. The next day her house was broken into, she was kicked viciously, and had a broken bone in her face. Burke acknowledged she had also received threatening phone calls. Burke claimed this was somehow connected to Paradiso and tried to get the incident into the trial.

Jean Day confided in her neighbor Louis Tontodonato in the fall of 1984. She told him the MSP had threatened her and wanted her to testify in a certain way. They arrested her on unrelated drug charges and threatened she would be prosecuted and never see her son again. She went into hiding in Somerville until she arrived at the courthouse on day eight of the trial. She told her neighbor she gave false and misleading testimony at the trial. Tontodonato gave a sworn statement filed with the Suffolk County Superior Court, along with investigator Slawsby’s, in a motion for a retrial on the Iannuzzi case. (The motion for retrial was denied by the same judge that presided over the trial, Judge Roger Donahue, not once, but twice.)

According to Burke, Trooper Palombo knew when the assault happened, and the prosecution team suspiciously had photographs of her injuries. The defense counsel knew nothing about the assault, and Paradiso was in jail when it happened. When Day arrived at the courthouse, the defense investigator took her to a private room to ask questions about what she remembered. Slawsby averred that shortly after he interviewed Day, Burke and Palombo escorted her down the hall. When court resumed after the lunch recess, Day was sworn in and changed her testimony. Reviewing transcripts of the grand jury and the trial show the crucial discrepancies enumerated by the investigator.

The stepsister’s testimony sharply contradicted with her grand jury testimony and the investigator’s interview in the morning on three crucial points. First, she could no longer remember the order her sister wore her clothing, in particular the pantyhose Bond alleged Paradiso struggled to remove. In the morning, she recalled the order in which her sister got dressed. Bond alleged Paradiso struggled to take off herpantyhose, but the victim was found with her clothing intact, and she was wearing a one-piece bodysuit with no snaps.

Jean Day and her mother arrived at the Doyle’s house before 7 a.m. Monday looking for Marie. Reports on the radio described a victim found on the bank of the Pine River they feared was Marie. Jean observed her stepsister’s packed belongings early Monday morning in the apartment she shared with Doyle. Jean remembered this detail in the morning with Slawsby, but could not recall that afternoon on the stand. The witness also noticed deep scratches on David Doyle’s hands Monday morning as the family gathered before going to the morgue to identify the body. Her trial testimony changed, and she was vague when she noticed Doyle’s severely scratched hands.

The defense introduced police reports and testimony at various hearings that revealed Doyle and his mother provided four explanations for the severe scratches on his hands, none of which matched with the injuries. Regardless, the state’s star witness at trial was the snitch, Robert Bond, who provided a false statement to the prosecutor's team about Paradiso, but the statement was sealed. He testified that Paradiso told him how he had killed Iannuzzi.

Judge Roger Donahue disallowed exculpatory evidence in a private conference with the attorneys. On the basis of hearsay, Donahue excluded Saugus police reports that named four witnesses who saw Marie Iannuzzi back in the bar around closing, a critical time after witnesses saw Paradiso hold the door for her. One witness was patron Carol Seracuse who took the stand five years after she spoke to police. She had no independent memory of her statement stating she spoke to Marie at 1:30 a.m. Judge Donahue rejected another police report of an interview conducted with a friend of David Doyle on July 16, 1981. The friend, David Dellaria, claimed Doyle confided murdering his girlfriend. The interview with Dellaria was detailed in a report that outlined other circumstantial evidence incriminating Doyle: scratches, blood on the step, and Doyle’s flight to New Jersey where he was arrested with a stolen airline ticket. Instead, Donahue displayed tremendous bias against Paradiso by stating his belief that the jury had sufficient evidence, based on Bond's testimony, to convict Paradiso of the charges of rape and murder.

Court records for the 1984 Iannuzzi murder trial revealed an inappropriate relationship between Trooper Palombo and the victim’s boyfriend, David Doyle. The lead officer on the case met with Doyle, a prime suspect in the crime, on numerous undocumented occasions. Palombo, once all these undocumented meetings with Doyle surfaced, testified at Paradiso’s trial that he did not consider Doyle a suspect. He said this despite all the eyewitnesses and circumstantial evidence pointing directly at Doyle – and away from Paradiso – for Marie Iannuzzi’s murder.

The jury found Paradiso guilty of second-degree murder and assault with intent to rape on July 22, 1984. Judge Donahue sentenced him to Walpole prison with a “from and after” sentence, a harsh and unusual sentence. Paradiso was sentenced to life for second degree murder, and not more than 20 years, but not less than 18, for assault with intent to rape. The second sentence was to be served after the sentence for murder.

Meanwhile, in Federal District Court in Rhode Island, the fraudulent bankruptcy case against Paradiso was coming to a conclusion. On April 9, 1985, Paradiso was convicted on three counts of bankruptcy fraud and sentenced to five years on each count on May 10, 1985. The Federal case charged that Paradiso lied on his bankruptcy application and did not report assets that were actually in his girlfriend’s (Candy Weyant) bank account, he did not claim the boat or the insurance money(also in Candy’s name), and that he misrepresented employment. The government never provided evidence that the self-employed shell fisherman earned income.

With Paradiso now convicted of murder, rape and bankruptcy fraud, Burke now wanted to hang Joan Webster’s death on him by linking evidence from her case to him.

Paradiso as Scapegoat

A search of Weyant’s house, where Paradiso had a room, in April of 1983 turned up a book that authorities claimed was Joan's textbook, Maya: Monuments of Civilization, by Pierre Ivanoff. It was a large, heavy coffee table type book, and Paradiso's edition was published by Grosset and Dunlap. The volume he possessed was a Reader’s Digest offering that was out of print in 1975, six years before Joan's flight. It would have been a white elephant difficult to obtain, and newer editions were available. A subsequent FBI search on July27, 1983 produced a red silk jewelry bag that authorities asserted belonged to Joan. In fact, it was part of a three-piece set, and Paradiso's girlfriend still retained the matching pieces.

Paradiso was X-rayed on November 30, 1981 for three small fragments in his finger. He indicated they were caused by sparks from a grind wheel when he attempted to polish an ammo shell he found. Two splinters had worked out, but X-ray films showed a splinter still embedded in his finger on December 22, 1981. Bond had claimed Paradiso had hurt his hand while murdering Joan, but the microscopic slivers were not consistent injuries with the alleged crime. Rather they were consistent with Paradiso's explanation, and the Massachusetts State Police recovered the ammo shell Paradiso indicated was the source of the fragments.

ADA Burke also claimed that authorities had recovered marine equipment from Paradiso’s boat, the alleged crime scene of Joan’s murder. Conflicting evidence came out in the proceedings held in theSuffolk County Superior Court during the Iannuzzi pretrial and the Federal court hearing bankruptcy charges. Testimony in the secret Federal grand jury negated Burke’s assertions in the highly publicized case the state was making. Testimony in ADA Burke’s courtroom indicated the Massachusetts State Police confiscated equipment manufactured by Danforth. In the secret grand jury session for the Federal case of bankruptcy, witnesses revealed Ray Jefferson manufactured the equipment from Paradiso’s boat, and the equipment was not interchangeable. In addition, FBI lab results produced nothing to connect Joan to the boat, but the results were kept confidential.

Corruption

The Boston FBI office was arguably the most corrupted office in the bureau's history. Ramifications are still being tried from the office's practice of protecting criminal informants such as Whitey Bulger, Stephen Flemmi, and Joe Barboza. There was a confidential source in Joan’s case. Burke and a fellow officer, Dave Moran, identified Palombo providing information that the FBI listed from a confidential source in their reports. The rampant corruption infecting the Boston office had not been exposed at the time the office was involved in Joan Webster's disappearance.

In addition to the misconduct still hidden in the FBI office in Boston, the Suffolk County D.A.'s office of Newman Flanagan was exposed for secret and duplicate files under the head of homicide, John Kiernan, in July 1991. The Kenneth Spinkston case brought Suffolk County convictions, prosecuted between 1980-1988, under scrutiny. Burke’s relentless pursuit of Leonard Paradiso was during the same period as numerous other questionable prosecutions out of that office.

Boston's history of wrongful convictions is well documented, and recovered documents reveal the same practices in the cases surrounding Leonard Paradiso. To secure Bond’s trial testimony, the state offered him enticements that were not disclosed to Paradiso’s defense or the public. Representatives of the Commonwealth offered inappropriate rewards that they had no authority to make: a lesser charge of manslaughter was promised. Sgt. Carmen Tammaro also discussed the Webster reward money, up to $50,000 was announced by the Websters, backed by George Webster’s employer ITT. Tammaro suggested the felon might be entitled to claim it. (No reward money was ever paid out.)

The two principle agencies involved in Joan's investigation, the Boston office of the FBI and the Suffolk County DA's office, were both exposed for serious misconduct.Unfortunately, their practices remained undetected and unchecked during the years of Joan’s investigation.

The Remains of Joan Webster

Karen Wolf Churgin, a veterinarian, was walking her dog on Chebacco Road in Hamilton on April 18, 1990. The area was remote and heavily wooded, and there were few residents in the isolated area. She discovered a human skull clogging a drainage ditch. A week long search of the area led to the grave of a young woman later positively identified through dental records as Joan Webster. Death was ruled a homicide caused by massive trauma from a blunt instrument to the head. The fatal blow left a 2” x 4” hole taking out the entire right side of the skull. The injury was inconsistent with the explanation proffered by informant Robert Bond, and local police now involved in the case speculated something more like a bat, wielded with enormous force, landed the blow.

The assailant stripped Joan Webster of all clothing, and discarded her body in a black plastic trash bag that had broken open beneath her. Cut logs were piled on top of her grave on more than one occasion. Jewelry, a gold serpentine neck chain and a gold amethyst ring, remained on the skeleton.

Bond's statement, claiming the body had been dumped in Boston Harbor, was now known to be false. This realization caused authorities to backpedal on the story to make pieces fit. Burke told the press in 1990 that Paradiso’s boat had a broken rudder, and it was doubtful the boat could have gone out. That fact was known in 1983, but the state promoted the harbor theory until Joan’s remains were found in 1990. Burke also suggested Bond’s statement may not have meant “way out” into the harbor even though that was the story the core group stuck to until the buried remains of the victim surfaced. To further conceal their tracks, authorities kept the condition of the remains confidential.

The location of the recovery was more than 30 miles from the alleged crime scene at Pier 7, but Burke maintained Paradiso murdered Joan Webster on the boat. Burke contended this despite the fact that undisclosed evidence, information available to authorities at the time, indicated the boat did not exist at the time Joan disappeared.

In The Paradiso Files: Boston’s Unknown Serial Killer, a book Burke wrote about the investigation into Joan Webster’s murder in 2008, he incredibly still maintains the boat was the scene of Joan’s murder, but now he has Paradiso moving the bloody body from the craft and travelling miles north to bury her in Hamilton, Massachusetts. In his book, Burke contradicts his informant’s statement. Bond asserted Paradiso deposited Joan’s belongings in the Saugus marsh three weeks after her murder even though they were recovered four days after she disappeared. Now Burke described Paradiso’s alleged route along the Lynn Marsh Road on the night of the murder, and tossed her purse in the marsh that night on his way north.

On July 13, 1990, Joan Webster was cremated at the request of her parents. This was still an open murder case. Although authorities had named Paradiso as the suspect for years, he was not involved in any inquest, never charged, and never provided autopsy findings he was entitled to as a suspect. The General Laws of Massachusetts, Rule 38, Section 14, specify a body not be released for cremation until there is no more judicial inquiry into the crime. In effect, the case was closed, but authorities continued to promote an implausible and impossible crime, supported by Joan’s parents, accusing Paradiso of Joan’s murder.

Stripping the Façade from Burke’s Case

Robert Bond appeared before the Massachusetts Parole Board on April 19, 2011 seeking parole for the murder of Mary Foreman. The open hearing was an opportunity for public statements. I am properly certified with the Department of Corrections, but Chairman Josh Wall denied me the opportunity to speak openly in front of the board. Bond had accumulated enemies throughout the penal system for his participation as a witness for the Commonwealth in other murder cases, namely the Iannuzzi and Webster cases. The board quickly changed the subject when Bond made that statement that he had testified for the Commonwealth in other murder cases. The convicted felon received a scathing review; he was described as deceptive, emotionless, and cold-blooded. The man lacked any remorse, was dishonest, and had the propensity to kill people. Robert Bond was the same individual Tim Burke, the Massachusetts State Police, and Joan’s parents promoted as a credible witness in their calculations against Leonard Paradiso

Newly appointed chairman Josh Wall left his position as first assistant D.A. out of Suffolk County, the office that had used Bond in their cause in the 1980s. Wall had been part of a blue ribbon task force delegated the responsibility to set standards correcting and preventing wrongful convictions out of the Suffolk County office. Wall was a 1982 Harvard graduate, Joan's fellow student when she disappeared, and he was also the former counterpart to first assistant D.A. John Dawley in Essex County, the current custodian responsible for Joan Webster's case.

One of Mary Foreman’s sisters offered to relinquish her time to allow my statement, but Wall still refused to allow me to speak on behalf of a member of my family. Wall's decision at the parole hearing, suppressing my victim impact statement supported with documents, disconnected the offender in front of them for his complicity in the Joan Webster investigation, and the public's awareness. I wanted the parole board to know the personal grief Bond’s false assertions about Joan’s death had caused Joan’s family and friends by diverting the investigation into her murder away from finding the real killer. Wall had received documents prior to the hearing that exposed the misconduct of named colleagues involved in Joan’s investigation. On January 18, 2012, the board unanimously denied parole to Bond

The current custodian of Joan's case files, the Essex County D.A.'s office, has denied access to its records in a 30-year-old mystery and indicated the case is still open. George and Eleanor Webster informed the D.A.’s office they did not relinquish their privacy rights, even though they publicly supported Tim Burke’s book and the Paradiso theory. (Eleanor Webster, known as Terry, died in June of 2010 of cancer.) The meeting my private investigator and I had with first Assistant D.A. John Dawley, Lt. Det. Norman Zuk, and two other members of the Massachusetts State Police on May 20, 2010 underscored the resistance by Essex County to resolve the case. Several documents were provided for their review.

I shared the suppressed composite drawing reconstructed from template numbers recorded in police files. The composite was suppressed by authorities, and the Websters were given the image on December 21, 1981. The drawing depicts the likeness of the man believed seen leaving Logan Airport with Joan. The image, compiled in December 1981 from a witness description, was not Leonard Paradiso, but the composite bears a striking resemblance to the lead officer involved in the case, Trooper Andrew Palombo.

Palombo, a Harley-Davidson aficionado, was 6’4” and 240 pounds. He was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1998. Joan's body was found not far from where Palombo lived at the time. It was a remote area that attracted hikers and bikers. There was also known criminal activity in this area, something an officer would know. The Hamilton police chief told my PI that Palombo knew the area. All the while Joan was buried there, Palombo was aggressively promoting she was murdered on a boat that didn't exist and dumped in Boston Harbor.

Actual records support the problem resolving Joan’s case was the investigation itself, and individuals closely involved are the ones to scrutinize in an independent review. The real evidence found in recovered documents exposes coerced, pressured, and enticed witnesses. The actual records reveal that evidence was manufactured and distorted. False information was provided to the Federal authorities. Exculpatory evidence was hidden in other cases and grand juries, and some evidence was suppressed entirely. Crucial testimony changed.

The composite, Bond’s interview on January 14, 1983, his written affidavit, and warrants filed with the court are among the many recovered documents that should be contained in Joan Webster's files in Essex County. Facts seriously conflict with Tim Burke's published book. Instead, the office publicly represented other cold murder cases are being examined based on Tim Burke's book, and cast suspicion on Paradiso posthumously for even more unresolved crimes. (Leonard Paradiso died on February 27, 2008, shortly after Burke’s book was published. He was moved from the Old Colony Correctional Facility to Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, a hospital that treats prison inmates. He continued to maintain his innocence for the assorted crimes Burke asserted including the murders of Marie Iannuzzi and Joan Webster.)

Joan Webster will never receive justice until there is an independent review of records. The theory promoted by the core principles does not withstand scrutiny of the factual records, and scapegoats are not acceptable for the brutal loss of a vibrant and valued life. Joan’s next of kin, George, her brother Steve, and her sister Anne, maintain Paradiso murdered Joan Webster despite any real evidence to connect him to the crime. The family has publicly stated it agrees with the authorities who investigated the case; the Websters effectively closed the case when they had Joan’s remains cremated in 1990. The family has instructed the D.A.’s office it does not want its privacy violated for an independent review in the unresolved murder. Sadly, I cannot find anything in recovered documents to justify their opinion. Murder is the state’s responsibility.

No prior examination of Joan’s tragic case ever studied the implausible excuse the state promoted for Joan’s loss. It was an excruciating ordeal to live through, and the injustice found in recovered records compounded the travesty and multiplied the number of victims.

The state’s misconduct in Joan Webster’s case suggests two possibilities: overzealous authorities serving up an excuse to satisfy public outcry, or the case was covered up to shield an offender from accountability. Neither is acceptable, but the fact is, Boston has a well-documented history of wrongful convictions. Recovered records open a new avenue of discovery into a lingering mystery, and the hope that truthful answers will finally bring closure to the case.

“There is no crueler tyranny than that which is exercised under cover of law, and with the colors of justice...” US vs. Jannotti, 673 F.2d 578, 614 (3d cir. 1982)