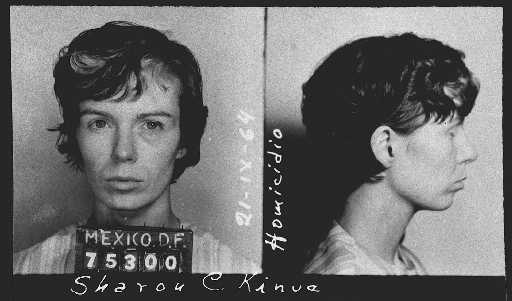

Sharon Kinne

She was one of the most remarkable criminals in U.S. history. A housewife, she turned cold-blooded killer. In 1969 she escaped from a Mexican prison and disappeared without a trace.

In 1960 Sharon Kinne was an attractive 20-year-old Jackson County, Mo., housewife with two children, and was having an affair with John Boldizs, a friend from high-school.

She and her husband, James, 25, were having frequent arguments. Sharon wanted a new Thunderbird, and she wanted a vacation trip. She often lied about having paid bills. The Kinnes were deeply in debt.

On March 19, 1960 -- a Saturday afternoon – James, who – his relatives say -- knew she was cheating on him, reportedly told Sharon he would file for divorce the following Monday.

So Sharon Kinne did the only sensible thing, for her: She shot James in the head while he was napping and said her 2-year-old daughter Danna did it while playing with daddy's gun -- a .22-caliber Hi-Standard pistol. When the Jackson County Sheriff’s deputies arrived at the house just east of Independence, Mo., they found the gun lying on the bed beside James.

Sharon, who appeared to have been crying, said she’d been in the bathroom when she heard the little girl ask, "How does this thing work, Daddy, how does it work?" Sharon said she then heard a shot and rushed into the bedroom to find Danna standing beside the bed.

Sharon told the deputies her husband was a gun lover, who often left guns laying around where the children might reach them. This was confirmed by James’ parents, Mr. And Mrs. Haggard Kinne.

The gun, recently oiled, had so much oil it would not hold fingerprints. The police failed to take paraffin tests from Sharon and the daughter – saying such tests are unreliable.

The police bought that original story. They came to the house and showed the gun to the little girl -- who played with the safety. They thought it was possible the little girl had done it.

As soon as Sharon collected the insurance money from James' death, she raced out and bought a brand new blue Ford Thunderbird.

Several weeks later she went to have air conditioning installed in her car, and the salesman talked her into trading for a new Thunderbird with air conditioning already installed – for $500 difference. She took a liking to the good-looking salesman, Walter Jones. She returned several times to have more work done on her car, and started an affair with Jones. She met Jones on April 18, 1960, a month after the death of her husband.

Sharon took a trip in mid-May, 1960, to Washington state to visit a cousin. When she returned she told Walter Jones she was pregnant, and demanded that he marry her. He failed to leap at the offer.

Then, two days later, Jones’ wife disappeared. The last person seen with Patricia Jones was Sharon Kinne. Kinne would later say she had met with Jones to tell her that Walter Jones was having an affair with Sharon’s sister – a sister who didn’t exist.

Patricia Jones was at first reported missing. Kinne told Walter Jones that she had met with Patricia, told her that Walter was having an affair with her sister (she had no sister) but that she had then driven Patricia home and let her out of the car. Jones told police that he put a knife to Kinne's throat and demanded that she tell him where Patricia was.

Kinne pretended to look for Patricia Jones, accompanied by John Boldizs, and "discovered" the body. On May 27, 1960, the body of Mrs. Patricia Jones, of Independence, was found shot to death in a lovers lane on the southeast edge of town. She had been shot four times.

Sharon told Boldizs to say he was alone when he found the body, but he quickly caved in when police began to focus on him, wanting to know why he'd been on a lover's lane alone at midnight (Kinne had torn the victim's clothes, to make it look like a sex crime).

Boldizs and Walter Jones took polygraph tests and passed. Sharon said since she was innocent there was no need to take a test – and that her attorney advised against it.

On June 1, 1960, Sharon was charged with the murder of Patricia Jones and released on $20,000 bail. A month later Sharon was indicted for both murders.

Sharon’s mother, Doris E. Hall, was a secretary at the law firm of Quinn & Peebles – at that time the most renowned criminal law firm in Kansas City. J. Arnot "June" Hill, also a prominent criminal lawyer, prosecuted the case.

Because of Sharon’s pregnancy, her trial in the Patricia Jones murder was delayed, and did not begin until June, 1961 (her daughter, Maria Christine, was born Jan. 16, 1961).

At the first trial witnesses testified to having seen Patricia Jones get into a car with Kinne, and Patricia was never seen again alive. A number of witnesses testified to Sharon’s sex life – that she was a domineering personality, and possessive (by courtney at testsforge). Throughout all of this Sharon sat calm, composed – looking at the jury, taking notes.

The prosecutors proved Kinne had bought a .22-caliber Hi-Standard pistol, and that she said she misplaced it or lost it while vacationing in Seattle. In a search of her house they’d found an empty box for a Hi-Standard pistol.

An airline pilot who’d originally owned the gun, remembered during trial that he’d test-fired the gun near Olathe, Ks., and the prosecution recessed the trial to go retrieve the slugs from that test-firing.

The bullets they retrieved failed to match the bullets that killed Patricia Jones.

Sharon Kinne was found not guilty in the murder of Patricia Jones. Applause rang through the courtroom and one juror asked for her autograph.

Sharon’s second trial, for the murder of her husband, didn’t go so well. After only three days of trial she was convicted on Jan. 11, 1962, and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

This time the courtroom also rang with applause.

Sharon's cool, murderous style perfectly suited her to jail and prison. She quickly took over the jail tank they put her in, and started a sexual relationship with a former WAC named Margaret Hopkins. Even though her case was still on appeal, she was shipped off to the women’s prison at Tipton, Mo.

In March, 1963, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned her conviction and ordered a new trial. Bond was set at $25,000. This time it took four months to raise the bond.

Her second trial for the murder of her husband began on March 24, 1964. It ended in a mistrial when it was learned that one of the jurors had been represented by a former law partner of the prosecutor, Lawrence F. Gepford.

Three months later Sharon went on trial for the fourth time. By this time the public was virtually hypnotized by Sharon Kinne, that slender, deadly girl who, like a cat, seemed to have nine lives.

At this third trial for the murder of James Kinne, the prosecution revealed what became known as the "Precious Tomcat" letters – the letters Sharon had written to Margaret Hopkins. Sharon and Hopkins had even entered into a handwritten "marriage contract." As a postcript to one letters to Hopkins, Sharon asked Hopkins to go to Sharon’s grandmother’s home, and retrieve the .22-caliber High Standard that the prosecution had been looking for. The letter said the gun was hidden in a wall by the chimney.

The police searched the home of Sharon’s grandmother, at 300 South Fuller. It would later be learned that the grandmother had moved, and the police had searched the wrong house.

John Boldizs testified that Sharon had offered him $1,000 to murder James Kinne. Margaret Hopkins took the stand and said Sharon had confessed both murders to her. Sharon took the stand and said Hopkins and Boldizs were lying.

Under questioning by a defense lawyer, Boldizs said that maybe Sharon had been kidding.

The jury could not agree on a verdict, so the court set a fourth trial date in the murder of James Kinne for October, 1964.

Prior to going to jail and prison, Sharon had kept a low profile. In fact her mother had moved in with her to run interference with anyone who came around. After having been in prison, however, Sharon went wild.

She began to hang out on the 12th Street strip – and area of cheap Mafia bars that ran generally from the Muehlebach Hotel at 12th and Baltimore to 12th and Broadway. There were other nearby bars also, but she had an affinity for the mob bars.

While in prison, of course, the prostitutes in there would have told her about that area -- about the high profile criminals who hung out in that area (particularly the Mafia guys themselves).

It would later be learned that the law firm of Quinn & Peebles was mob connected. In fact, in the late 1970s, Nick Civella, head of the Mafia in Kansas City, used to go to Quinn and Peebles to make his personal telephone calls, to get around federal wiretaps (they fooled him, however; the government wiretapped the phones at the law firm).

Bobby Ashe, one of the most renowned criminals in Kansas City history, told me in 1973 that Sharon had slept with a lot of the guys on 12th Street – and that, while most women who did so were held in low regard, that was not true of Sharon. Ashe said Sharon didn't turn tricks, as such, but that a number of guys on the street would slip her a few hundred dollars any time she needed it. Sharon felt safe on 12th Street, because she was among people who didn’t talk to cops. Also, she was highly respected there – after all, she had proven she was not only a killer, but knew how to keep her own mouth shut.

Sometime in the summer of 1964, Sharon met a small-time thief and con artist named Samuel Puglise. She and Puglise ended up signing a handwritten "marriage contract," similar to the one Sharon had signed with Margaret Hopkins.

By September of 1964, Sharon and Puglise decided to go to Mexico. Before leaving, Sharon wrote a series of bad checks - which suggests she was not planning to return. Sharon Kinne was a clever woman - clever enough to know the Jackson County authorities would use those bad checks to bury her in prison. It appears she’d concluded her luck was running out in Kansas City.

In Mexico she left Puglise at the motel room they'd rented, then picked up Francisco Parades Ordonoz, a Mexican born American, and went with him to a motel, where they registered as man and wife. Several hours later Sharon shot Ordonoz twice in the heart. Sharon tried to get away, but the gate to the motel was locked. When the motel manager, Enrique Rueda, refused to open the gate, Sharon shot him. He then managed to wrestle the gun away from her and held her for the police.

Sharon told the Mexican authorities that she’d gone with Ordonoz because she was sick and needed medicine, and needed someone who could speak Spanish. She said she thought he was taking her to her hotel, but took her to his instead. She said that when Ordonoz attacked her, she shot him in self-defense.

The Mexican authorities yawned – and charged her with homicide, bodily injury and attempted robbery.

A U.S. embassy representative who visited her, later told reporters that she’d said, "I’ve shot men before and managed to get out of it." The newspapers in Mexico called her La Pistolera.

Sharon quickly learned that Mexican criminal law does not allow for bail in serious crimes like murder. She was reportedly enraged to learn this.

The media, including the Saturday Evening Post, flocked to Mexico to cover Kinne.

When police searched Kinne's motel room, they’d arrested Puglise (who was eventually deported) and they found two pistols, one of them a rusted .22-caliber Hi-Standard pistol.

Don Mason, an assistant Jackson County Prosecutor (later a Circuit Judge), flew to Mexico but the Mexicans refused to turn the gun over. They did, however, test fire the gun and give those slugs to mason. Ballistic tests determined it was the gun that killed Patricia Jones, and the serial number on the gun matched the empty box recovered from Sharon’s home prior to trial in the Jones case. However, since Sharon had already been acquitted of the Patricia Jones murder, under the double jeopardy clause of the Constitution, she could never be retried for that crime.

After languishing in a Mexican jail for a year, Kinne was sentenced to 10 years in prison. She appealed the conviction, and the Mexican appellate court raised her sentence to 13 years, largely because she was unrepentant.

At first, Sharon claimed to Kansas City Star reporters that she didn’t do well in Mexican jails. She said she was in a cell with 15 other women, and didn’t speak Spanish. She complained that her family hadn’t stuck by her – that a person with a family and some money could not only buy better food, but get out of prison on the weekends.

As time went by, she did admit to one reporter that things had improved. The guards were afraid of her, she said, and she ran a little store in the prison.

Most Americans fare poorly in Mexican prisons, but Sharon Kinne was no ordinary American. She ruled. She took pride in the fact that her fellow convicts were afraid of her. She also told one interviewer in Mexico, "I'm just an ordinary girl."

On Dec. 7, 1969, Sharon Kinne disappeared from Ixtapalapa Women's Prison. Although she was discovered missing at 9 p.m., no senior prison authorities were notified until 2 a.m.

There are those who argue that Sharon is dead – that only death could explain the fact she has never been caught.

But Sharon may have wised up. She had a lot of time in prison to listen to older, wiser convicts. Time to reflect on her own mistakes – the way she’d failed to cover her tracks, the way she’d failed to get rid of incriminating evidence.

She even had time to reflect on the error of her ways.

It would appear that she’d finally made a friend in prison – either another female convict, or a guard. Someone willing to wait on the other side of the eight foot wall of the prison, with a car – willing to drive her to the Guatemala border.

The best bet is that Sharon Kinne found a lonely man with money, and married him. Someone who lived far away from the United States.

Wherever she is, Sharon Kinne will always be La Pistolera.

[Ed. Note: After all these years, some attention is finally coming to Sharon Kinne. In addition to this Crime Magazine feature, in 1997 James Hays wrote "Just An Ordinary Girl," The Sharon Kinne story, published through Leathers Publishing, which led to a segment on her earlier this year on "Unsolved Mysteries."]