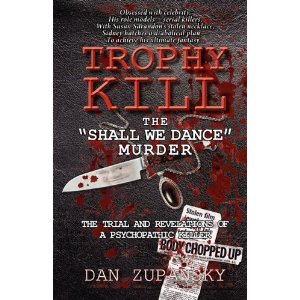

An excerpt from Dan Zupansky’s true crime book Trophy Kill: The Shall We Dance Murder which Prohyptikon Publishing-Toronto released in April 2010. All rights reserved. www.TrophyKill.tv

By Dan Zupansky

Winnipeg in the province of Manitoba is a cosmopolitan city with a rich history, the capital of the province and the eighth largest city in Canada. Situated in the Red River Valley in the geographical center of North America, it covers over 145 square miles. The population in 2003 was almost 700,000 people, comparable in size and population to the city of Seattle, Washington, without Seattle’s vastly more populated surrounding suburban area.

For decades the license plate for the province read “Friendly Manitoba” and for many years running, Winnipeg has held the distinction of having the highest per capita murder rate in Canada.

The Miramax movie Chicago, starring Richard Gere, Renee Zellweger and Catherine Zeta-Jones, won six Oscars in 2002.It had been primarily shot in Toronto. Clearly hoping to benefit from the success of Chicago, Miramax began production on another dance-themed movie called Shall We Dance starring Jennifer Lopez, Susan Sarandon and again Richard Gere—it was to have been filmed in Toronto also.

In March 2003, reports of health care workers with unexplained pneumonia in Vietnam and Toronto initiated an international investigation of the infection that came to be known as SARS, or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. During the outbreak, transmissions in hospitals and infection persisted in Toronto and Taiwan. Consequently by April 2003, the World Health Organization imposed an international travel ban on Toronto.

Near the end of May 2003, a new cluster of SARS cases was detected in Toronto.

With the definite possible health risks associated with filming in Toronto, which was to start in June, Miramax decided to move the filming of Shall We Dance to Winnipeg.

The ravenous paparazzi descended on Winnipeg anxious for any photo or any story involving Jennifer Lopez and fellow cast members, Susan Sarandon and Richard Gere. The paparazzo’s focus was on Jennifer Lopez, however, even though Sarandon and Gere were huge stars in their own right¾Lopez’s performing career and especially her personal life had captured the imagination of millions of fans everywhere.

There was a definite buzz in the air in Winnipeg since the movie began shooting the second week of June. Hundreds of actor and dancer hopefuls had tried out for coveted parts as extras in the movie. Most every day, the local papers featured on their front pages photographs of the stars waving to fans, shaking hands and enthusiastically signing autographs. A legion of young movie fans had just been let out for summer holidays.

It was Canada Day, July 1, 2003; a man named Robin Robert Greene was in Winnipeg. He was visiting from the Shoal Lake Reserve in Ontario, a couple of hours drive east of Winnipeg, just the other side of the Manitoba border. Greene was a 38-year old aboriginal man who had the free time and wanted to visit Winnipeg for the July 1st Canada Day festivities. He was anxious to hear the bands that were to play at The Forks and later to see the fireworks display.

Robin Greene was outside early that morning of July 1. The Shall We Dance film crew was set up a few blocks away from The Forks at an outdoor location near the Provincial Legislative Building. Filming had begun at 8 a.m. and by around 10 a.m. fans had gathered near the outdoor site trying to get a glimpse of one of the stars of the movie.

Susan Sarandon was in her trailer, changing clothes after having filmed some scenes. Her personal assistant, Maria, was with her. Sarandon removed her two gold earrings; her engraved silver bracelet and the antique gold necklace with pendant and put them on the counter. Her assistant gathered the jewelry and put it in a Ziploc bag and then placed it into one of the cupboards. The two then left the trailer.

Robin Greene was out walking near the area and came upon a group of anxious fans assembled behind a barricade manned by a half-dozen security personnel, about a block from the outdoor movie location. Greene had to ask someone what all the excitement was about. He was told that people were there to see Richard Gere and Susan Sarandon. He hung with the excited crowd for a while but no one had a chance to see Sarandon, Gere or any of the other stars of the movie.

Greene eventually wandered away from the assembled crowd, walked a block and a half or so north and then came upon a group of trailers parked side by side. He walked around the trailers for a few minutes and didn’t notice any security staff and decided to enter the biggest and nicest trailer of the many that were there.

Inside were changes of clothes, a small wall mounted television, a small bar fridge and some magazines. Greene searched the room quickly and found the Ziploc bag with jewelry in one of the cupboards. He grabbed the Ziploc bag, stuffed it into his pant pocket and exited the trailer. He walked quickly, heading downtown to Main Street.

A little while later Sarandon's assistant went to the trailer to drop off some clothing and was surprised to discover one of Sarandon’s gold earrings on the floor. Thinking it unusual that Sarandon would have returned to the trailer to retrieve her jewelry—she went to the set and told Sarandon that she had found one of her earrings on the floor of the trailer. Sarandon, confused, stated that she hadn’t been back there since taking off the jewelry. They both rushed to the trailer and realized that someone must have stolen the jewelry and dropped the one gold earring on the floor while leaving. Sarandon contacted security on set and they in turn notified Winnipeg Police.

It was about 11 in the morning by the time Robin Greene made his way to The Woodbine, an older drinking establishment on Main Street¾right next door to Ted Motyka Dance Studio, where Richard Gere was spending most of his off camera time getting what he felt was necessary extra dance rehearsals. Once inside the bar Greene moved from table to table asking patrons if they would like to buy a gold necklace for $15.

Sidney Teerhuis, a 33-year-old aboriginal man, had been in the bar since just after 9 that morning. He was close to 5’8 and weighed about 220 pounds. He was overweight with a chubby face and a third chin. He wore silver colored thin, wire rimmed glasses and had short, slightly wavy, dark brown hair. He was clean-shaven and had a boyish, dimpled face.

Teerhuis had been employed as a chef for almost 10 years in Vancouver and Edmonton and most recently had worked in Kenora, Ontario. He had just lost his job there and after a long absence was back in Winnipeg where he was originally raised. He was planning to return to Edmonton as soon as he could. He had been up all night drinking alcohol and smoking crack cocaine.

Teerhuis was sitting with a man and a woman at a table when Greene approached them to buy a gold necklace for $15. Teerhuis told Greene to have a seat next to him while he examined the gold necklace closely. It was a thick gold chain with amber colored pendant attached to a thin gold bar. It looked quite old. Teerhuis declined to buy it but convinced Greene to put the necklace away and poured half a beer in a glass for him to drink.

Greene put his hand on Teerhuis’s knee and smiled. Teerhuis found Greene attractive and after drinking and talking for a while they decided to leave the Woodbine and go to his room at the Royal Albert Arms¾Teerhuis told Greene that he had beer in his room to drink.

Once upstairs in the room, Teerhuis asked Greene to sit down on the chair and take off his clothes. Greene was around 5’8 in height and weighed about 150 pounds. He was average weight and not especially muscular. He had long straight jet-black hair, halfway down his back. Teerhuis watched him undress completely and then offered him a beer as Greene sat naked and they talked.

Teerhuis had three disposable cameras in the room and took provocative photos of Greene in different poses—some were of him modeling underwear and others of him naked lying in the bathtub. Teerhuis asked Greene if he wanted to move in with him, that way they could have sex every night. Greene replied enthusiastically, “Yes.”

They kissed and held each other. Greene pulled Susan Sarandon’s gold necklace from his pant pocket and placed it around Teerhuis’s neck. Teerhuis moved in front of the dresser mirror to see how the necklace looked. It was obviously a women’s necklace. He thought that Greene’s gesture though was “kind of sweet.”

Eventually Teerhuis took off the necklace and put in on the dresser. They both had by now warm beer and Greene commented that it was a beautiful day, and that they should get outside. It was getting hot. Teerhuis locked the door and he and Greene left the hotel.

They walked a few blocks north, stopped and bought some beer at the Windsor Hotel and headed to the Millennium Library, a couple of blocks away. The newly built library was a fine example of modern architecture featuring a grand courtyard with many flower gardens, numerous high-back benches and a huge water fountain. They sat in the shade of a large elm tree and took a few swigs of their beers. Greene took off his white t-shirt and they kissed as a steady breeze provided some relief from the increasing heat.

After a short stay outside the library, they continued walking to the Assiniboine River and finally made it to Bonnycastle Park, situated behind the Hotel Fort Garry’s Royal Crown Restaurant. The Park on Assinibione Avenue just off Main Street is a popular meeting place for homosexuals.

The barricades and the security for Shall We Dance were just a few blocks down the street.

Greene and Teerhuis sat at a picnic table talking and drinking beer. The park was well maintained, with plenty of colorful flowerbeds and neatly trimmed hedges. The grass was freshly cut and clipped around the cement sidewalk. An older couple lounged on one of the park benches while Teerhuis and Greene sat there quietly, soaking up the sun.

Greene got up, stretched and slowly sauntered down toward the river. Teerhuis watched his new friend stop to chat with a young, blond guy. They talked for a few minutes and then Greene walked back to the picnic table and told Teerhuis the young guy was a hustler, and that he wanted to take him back to the room. Teerhuis refused, saying that the guy was too young and suggested that just the two of them should head back to the hotel. Greene agreed.

By then it was late afternoon, around 5 p..m.¾numerous cars adorned with Canadian flags, packed with families, headed to the Forks for the July 1st festivities. The revelers drove past the two men as they walked northbound on Main Street to the Royal Albert Hotel. It was stifling hot by now, as they slowly made their way back to Teerhuis’s room.

They entered the hotel lobby and walked towards the elevator just a few feet away from the bar entrance.

Teerhuis spotted Dianne and motioned Greene to follow him and they walked over to the stand-up bar where she was working. He introduced Greene as his cousin so that she wouldn’t suspect that he was gay. Teerhuis was a self-avowed homosexual but when in bars in downtown Winnipeg, he liked to keep that to himself.

Teerhuis then asked Dianne, “Can you keep an eye on him? I’m going to get some ice.” She nodded yes. He was worried that his new acquaintance might get into trouble or might just wander off. He walked through the bar to take the stairs to the basement.

While he was gone Dianne noticed Teerhuis’s “cousin” was swaying back and forth¾quite unsteady on his feet.

Teerhuis was gone a few minutes and returned with a bucket of ice.

They said their goodbyes to Dianne and walked to the elevator heading to room 309. Teerhuis planned to have a few more drinks and have some more sex¾after all the night was still young.

The next morning, July 2, around 9:30 a.m., Sidney Teerhuis walked through the visitor’s entrance into the Winnipeg Remand Center. The Remand Center sits directly across from the Law Courts Building and is the facility where those persons currently in custody attending trials or awaiting bail hearings are held. Two male guards were at the front desk and when Teerhuis got to the desk one of the guards asked,

"Can I help you Sir?”

Teerhuis replied matter-of-factly, "I found a body chopped up in my bathtub. I’ve turned myself in because I’ve killed somebody.”

The stunned guard replied, "Don't say another word. I’m not the person you should be telling this to!” He then handed the phone to Teerhuis, gave him the number for the Public Safety Building and instructed him to call.

The operator on the line Robyn Sabanski answered, “Winnipeg police, how can I help you?”

Teerhuis calmly replied, “My name is Sidney Teerhuis and I killed someone yesterday.”

“How did you do it?”

“I chopped up the guy. I blacked out and when I woke up I found the body in the bathtub.”

“What type of weapon did you use to kill the victim?”

“I used a knife.”

“Where is the knife now?

“I left it on the floor of the bathroom.”

“Where did this occur?”

“The Royal Albert Arms Hotel, room 309.”

“And where are you now?”

“The Remand Center.”

“Sir, police officers are on their way.”

About 20 minutes or so had elapsed by the time two police officers, August Marin and his partner Sylvia Shroeder, arrived at the Remand Center. Marin had been a cop in Winnipeg for almost eight years; Shroeder had been one for four years. As soon as they walked into the facility the guard at the front desk pointed to Teerhuis sitting on a small couch not too far from the entrance. They approached him and asked him to explain his story.

Besides what the two officers had already been informed of by the 911 operator, Teerhuis told them that he had met the victim, they had gone to his room for drinks and consensual sex—and eventually he had passed out intoxicated. When he awoke he went to the washroom and in the bathtub was the dismembered body. No more details were given to the officers and the three of them proceeded to the Royal Albert Arms Hotel and Teerhuis's room.

The hotel was not very far from the Remand Center by car and they arrived there in a few minutes. The hotel was built in 1913, making it one of the oldest hotels in Winnipeg. The hotel had seen better days; the rooms were typically rented to welfare recipients and low-income residents. Besides catering to the hotel residents, the beer-soaked barroom was also a fixture of the punk and hardcore metal music scene for years in Winnipeg.

Constable Beach, a beat patrol officer joined Shroeder and Marin at the hotel and the three officers and Teerhuis went through the front entrance, past the now dark, closed barroom to the elevator and up to the third floor. The halls were quite narrow and the floors uneven¾the walls covered with graffiti¾the room doors haphazardly painted off-white. Officer Marin asked Teerhuis for the key to the room and Teerhuis handed it to him. The cleaning lady was down the hall, cleaning another tenant’s suite.

Marin opened the room door and walked in first and officer Shroeder followed. Constable Beach remained in the hallway with Teerhuis. It was a small room, littered with beer bottles and numerous pairs of bloodstained underwear. Shroeder found a bed sheet on the floor covered in blood and the mattress had several deep knife cuts and was soaked with blood.

There was blood splatter all over the wall by the bed and the wall leading to the washroom. Marin quickly completed looking about the room and proceeded to the washroom. The light shonein from the washroom window and when he pushed open the door—he froze.

In the antique claw-foot bathtub Robin Greene was displayed, lying on his back facing the doorway. He had been dismembered and posed crudely reassembled. The decapitated head with long, straight coarse black hair sat atop the neck and torso. One of the eyeballs was gone and the other punctured. The mouth was frozen wide open.

The body was sawn in half at the waist. The severed forearms were positioned close to the elbows as well as the severed legs, which had been chopped just below the knees. The penis and testicles were removed together and placed in their usual position. The chest had dozens of deep stab wounds carved in a figure-eight pattern. The right nipple was cut off and the right forearm and hand partially dissected.

There was one huge cut from the neck clear to the waist and the chest and abdominal cavity were completely empty. Flesh hung from the two ribcages. The skin’s color was an ashen gray. All of the internal organs, the intestines¾everything that normally would have been in a body¾were gone. There was no blood inside the cavity or on any of the body parts.

Officer Marin stood there for two or three minutes transfixed—unable to move or say anything. His mind could simply not process what he was witnessing. Despite the fact that he had grown up in rough-and-tumble Winnipeg, despite his extensive police training and almost eight years working the streets of Winnipeg, despite having being told by Teerhuis that there would be a chopped up body in the bathtub, the scene was overwhelming. The big, strong, tough and trained veteran officer found himself short of breath, his chest tight, sweating, shaking and needing to vomit. The sight and smell of the rotting corpse, surrounded by a horde of flies began to finally snap him back to reality. Initial shock turned to cold-hard recognition and then finally¾revulsion.

He finally stumbled out of the washroom, to the main room and then out into the hallway. He tried his best to compose himself, steadying himself in the doorway, trying to catch his breath and finally told Officer Beach, “Cuff him,” and he did. Referring to the washroom, he told his partner, “Don’t go inside there. You really don’t need to see that.” Officer Marin locked the door and gave the key to Officer Beach so he could remain, keeping the room secure. The two officers and Teerhuis walked to the elevator and traveled downstairs to the lobby and then outside to the police car.

Officer Shroeder placed Teerhuis in the backseat and then concerned, asked her partner, "Are you okay?” Shaking, the officer wiped the tears from his face and replied, "No, not after seeing something like that!”

After officer Shroeder had called headquarters to report the murder and arrest, she and her shell-shocked partner and Teerhuis sat together in the police car. Officer Marin asked Teerhuis if he wanted to contact a lawyer and Teerhis said that he did.

Soon the coroner's van pulled up. Three Ford Crown Victoria police cars showed up shortly after the coroner arrived and four crime scene technicians, the coroner, Shroeder and Marin entered the hotel and went to room 309. A crowd had started to gather outside the hotel, soon after CTV News showed up. Not long after the other television news organizations began to arrive and with them came the many curious onlookers¾someone was heard asking if the scene was being filmed, as part of a movie.

Sidney Teerhuis sat handcuffed in the backseat of the police car taking in the whole scene—no one seemed to really take notice of him sitting quietly there in the cop car. After about 10 minutes or so, the two officers appeared from the hotel and returned to the cruiser. The three of them then proceeded in silence to the Public Safety Building.

Crime scene investigators searching the room had discovered Susan Sarandon’s stolen gold necklace in the midst of the murder-horror spectacle.

I arrived back in Winnipeg on the fourth of July after spending Canada Day in Thunder Bay and saw the Winnipeg Sun newspaper with the headline “VICTIM CUT IN PIECES, Stolen Film Jewelry In Bizarre Tale Of Murder.” The following days saw the murder/dismemberment story make the front pages and then on July 12Sidney Teerhuis made again the front page, with his smiling face and the headline “I AM NOT A MONSTER” and inside another caption, “I’m Not Jeffrey Dahmer” and then on page 3, with the headline, “ROYAL ALBERT HELL, Accused Killer Has No Recall Of Grisly Events.”

I read the story about the gruesome murder and the statements made by Teerhuis saying he had passed out and had no memory of the killing. I cut the articles from the newspapers and put them with the other related clippings that I had been saving. This case was of particular interest to me—I was producing and hosting a talk radio program called “Off the Cuff” on the University of Manitoba Radio Station CJUM for almost three and a half years, and had worked as chair of Media and Policy Affairs for a Winnipeg-based law-reform group called People for Justice.

I was a vocal critic of the Canadian judicial system and I felt this case would demonstrate clearly one of the most important issues raised by People for Justice. Based on the fact that Teerhuis claimed to not recall anything whatsoever of the killing due to intoxication—I believed that the prosecution would not be able to successfully convict him of murder. The prosecution would have to settle for a manslaughter conviction.

With double credit given for pre-trial custody and sentences typically around 10 years with one-third time off for good behavior¾even without parole, which he would be eligible for after serving one third of his sentence¾Teerhuis would be out in four years or less.

I saw murder charges routinely reduced to manslaughter via plea agreements, supposedly because of the difficulty successfully prosecuting murder. Right from the first time I read about Teerhuis and this case, it seemed absolutely absurd that anyone would accept that a person could do such an incredible act and not be cognizant of his actions. Given the fact that there were no eyewitnesses to the killing, I felt the story Teerhuis had put forth about the killing would be the only story ever told.

***

Don Abbott was an old high school acquaintance from Thunder Bay who had moved to Winnipeg a couple of years earlier than I had which was 1994. Over the past few years we had bumped into each other occasionally, and a couple of different times in August and September of 2003, he had visited me at my home.

In November I received a phone call from Abbott who was calling from the Winnipeg Remand Center. He explained that he had been charged with two criminal offences and went on to claim innocence regarding the more serious charge. I tended to believe him based on his explanation and I agreed to let him call me from jail. We talked every few days.

Abbott was to be in jail for Christmas. Despite his predicament – on the phone he seemed to be faring well – I was returning to Thunder Bay to spend the holidays with family and friends.

One day, a couple of weeks after Christmas, I received a phone call from Abbott and he asked me to guess who was in his jail range with him. I asked him whom he was referring to and he said "Sidney Teerhuis.” The name didn't ring a bell immediately until Abbott explained, "Sidney Teerhuis¾he’s the person who had chopped up that guy at the Royal Albert!”

I was surprised and immediately expressed my interest in interviewing Teerhuis and asked Abbott to see if he could somehow arrange an interview.

A few days later Abbott called to say that Teerhuis would be interested in being interviewed at some point in the future. I told Abbott to tell Teerhuis that I was interested in his story and the murder trial.

I pondered Teerhuis's case and this unexpected prospect of a unique journalistic opportunity. I began to think much more ambitiously and decided to write a book. I discussed the idea with Abbott and asked him what he thought. I told him that¾based solely on the details of the murder and the celebrity angle¾there would be many people that would be interested in the story. I believed that offering a share of the potential profits from the sale of the proposed book would motivate both Abbott and Teerhuis more effectively than anything else would.

Legislation was just being drafted by government in the province to prevent criminals from profiting from the notoriety of their crimes.

Abbott approached Teerhuis with my proposal and Teerhuis told Abbott he was interested in participating in the book project.

I asked Abbott to request to share a cell with Teerhuis so he would be able to begin the research needed for the project.

The next day the request to share a cell with Teerhuis was granted.

Abbott and Teerhuis used their time together to document Teerhuis's life from the time he was a child living in Winnipeg, up to and including his time spent in Vancouver and Edmonton. Abbott was assigned the task of befriending Teerhuis and encouraging him to write about his past. Anything else he could glean by living with him everyday could turn out to be important.

Within a few weeks Teerhuis asked if I wanted to visit him in person. I told him that I was interested. He gave me the phone number to call so I could book a visit.

I called the next day and provided my particulars.

The following day I called and booked a visit for March 9, 2004.

I had no idea what to expect. I knew what he looked like and what crime he had committed. I knew that he wanted to talk.

I began to interview Teerhuis by telephone regularly, but more importantly he started to send me letters and with each letter he revealed a little bit more about himself and his life up to the present time. He was very candid about all aspects of his personal life.

In October 2004 I received a letter that shed much more light on the facts surrounding the case. As a result, I became much more aggressive and probing with my questions.

Each subsequent letter I received gradually revealed that Teerhuis could definitely remember the actual killing, dismemberment and whereabouts of the missing internal organs. I kept pushing for more information, for more answers.

In December, I received two letters from Teerhuis, which included detailed drawings and very graphic descriptions of what really transpired in that hotel room that fateful night.

Teerhuis had instructed me many months before that he wanted the information he had sent me to be revealed after his murder trial had been decided. I had also been led to believe that the information he had provided to me was of an exclusive nature. It seemed amazing that I would have all this information that neither the prosecuting Crown Attorney, the police, Teerhuis’s lawyer nor the defense psychiatrist would know anything about. Armed with this crucial evidence, I felt certain it would greatly alter the outcome of his trial if this information were to be known. I had definitely gained Teerhuis’s trust but I was still shocked that he had revealed as much as he did, which was tantamount to a written confession, an absolute admission of guilt—and much, much more.

The defense attorney representing Teerhuis was Greg Brodsky. Brodsky is a Winnipeg native, a 49-year veteran of criminal law. He has by his own count, defended accused in more murder trials than any other attorney in the English-speaking world. He is known especially for his unapologetic defense of killers and the most heinous of offenders—he worked for the defense in the Paul Bernardo trial. His impressive success rate and effective courtroom tactics have earned him a formidable reputation in the Canadian judicial system.

What I thought would happen at the trial is despite the absurdity of Teerhuis's claim that he had passed out and could not remember anything of the commission of this murder/horror spectacle—Mr. Brodsky would try to prove that very claim.

I found myself directly involved in a modern day murder mystery, not the classic "who done it?” But rather, "why had he done it?” Teerhuis gave me crucial information in bits and pieces, turning this into what seemed an elaborate puzzle. He was more than happy to cooperate, never really refusing to answer any question put to him, only deferring some questions to a later date—with the assurance that he would answer them in the foreseeable future.

In many ways this crime didn't seem to make sense despite all the information Teerhuis had given me in regard to the motive—I thought that there might be more to the story.

As I had requested, Teerhuis had referred to in his most recent letter the interrogation at the police station, which occurred after he was formally charged with murder. The police had questioned him about other murders in Vancouver and Edmonton, which involved several murdered young males that shared striking similarities regarding the killing and dismemberment. According to Teerhuis, one of the detectives involved with the questioning had became so frustrated with Teerhuis’s denials that he finally insisted that Teerhuis had killed all the young men.

Teerhuis had also told me about a serial killer from England named Dennis Nilsen who had murdered and dismembered 15 men and about best selling author Ann Rule who had written 22 books about serial killers and their cases, starting with Ted Bundy.

I researched Nilsen’s crimes to learn whatever I could. Maybe there was something specific that Teerhuis wanted me to discover, some shared characteristic, something that Nilsen had done that had influenced Teerhuis. I thought there was good reason why Teerhuis had seemingly directed me to two “experts” on serial murder.

I thought about what the police had said as I began drafting much different questions to ask Teerhuis¾bearing in mind the distinct probability that he had killed before. These new questions elicited the following written response from Teerhuis to me:

You seem to be so focused on the missing internal organs, so here is a little quiz: Only one of these statements is true:

What did I do with Robin Greene’s internal organs?

Were they?

a) Flushed down the toilet

b) Did I sell them to George for fifty dollars?

c) Did I eat them in a cannibalistic ritual?

d) Were they tossed in a BFI dumpster near H.S.C. (Health Sciences Centre)?

e) Were some tossed in a vacant lot and a dumpster near H.S.C.?

Only one of these statements is true, what do you personally think I did with Greene’s organs? Be realistic.

2. Greene’s murder is similar to whom: A) Dahmer B) Zodiac Killer C) John Wayne Gacy D) Dennis Nilsen

3. Do you think I have the characteristics of a serial killer? [] Yes [] No

4. Do you think I enjoyed the entire event (the murder stabbing death of Greene and the necrophilia and dismemberment) from beginning to end? [] Yes [] No [] Not sure

When you kill someone you experience a frenzy, a vehemence for what cannot be changed; the triumphs and trophies Greene’s physical body had to offer when I carved him up, having sex with a dead body was more powerful than anything you could fathom. The poetry of Greene’s viscera, the inexplicable beauty of his intestines elaborately coiled and folded, the rich aroma of fresh human meat, the sound of stainless steel cutting into bone, ripping out the lungs with my bare hands. When Greene was sawed in half, the shreds of flesh hung from his ribcage like colorless frond. Randomly stabbing his corpse, butchering him for the mere pleasure of it, because I can (when you cut off a human arm or leg, then hold it and admire it, you are overwhelmed with this ideology that the victim was ultimately sacrificed for the right reasons).

When I butchered Greene’s body, watching the steel blade enter the body and the sensation of pulling it out again was beyond any moral connection. I treated the corpse like a side of beef, like Greene was a dead animal and portioned him like a giant turkey, cutting off the arms and legs.

Epilogue

Susan Sarandon’s stolen jewelry was the motive for Teerhuis’s murder-horror spectacle. Armed with the jewelry he decided to end his reign of horror with the opportunity that presented itself to him. He was an experienced serial killer¾disposing completely of his previous victims¾leaving absolutely no trace of any evidence linking him to any murder. When he discovered that he was in possession of Sarandon’s jewelry he hatched a plan to gain the fame he so desperately craved.

Very carefully and surgically dismembering his victim; staging and posing the reassembled ghastly creation, minus all of the internal organs¾then calmly walking into a police station to claim that he had passed out and when he awoke found the man cut into pieces.

The grisly horror spectacle alongside movie star Susan Sarandon’s stolen jewelry left for police to discover alone should have gained him the fame he so badly needed but he went on to grant interviews and write letters to Winnipeg journalists but no one wanted or dared to know the entire story.

I happened to get an opportunity to discover the truth and I took it.

Dan Zupansky is the author of the true crime book Trophy Kill: The Shall We Dance Murder and the producer and host of a weekly live talk radio program True Murder: The Most Shocking Killers in True Crime History and the Authors That Have Written About Them on BlogTalkRadio, Wednesdays at 8:00 p.m. CST.

Go to www.TrophyKill.tv

And join Dan every week for his talk radio program True Murder: The Most Shocking Killers in True Crime History and the Authors That Have Written About Them on http://www.blogtalkradio.com/dan-zupansky1

Also check out videos Trophy Kill and The Shall We Dance Murder on YouTube